It was time for me read Dracula again.

After all, it had been more than a few years since I’d last read the book cover to cover, and with all my work related to the novel, it was time to get a fresh perspective. Then, as I was revisiting the first chapter, a thought struck me: If I’d been reading Dracula as an assignment, that is, if I was a reader for a Hollywood Studio and been asked to read and give a report for this novel, what kind of coverage would I provide?

One of my areas of interest in film school (and with subsequent courses from other teachers) is story analysis. A common job film school grads move into after graduation is that of being a “reader” for production companies—in this job, one reads a script or novel and produces a synopsis, summarizing the story while bringing up its strengths and flaws, and then recommending whether it should be considered for a potential movie adaptation.

Most—no, I’d say all of these readers are also screenwriters, so the job of a reader is good for many reasons: 1) It forces you read a lot of books, which any writing teacher will tell you is essential for being a good writer yourself, 2) You see what kinds of stories are being sold to studios, and 3) It sharpens your own skills to see what works and what doesn’t.

With my interest in story analysis, a question that intrigued me even as I was reading the first chapter of this book is: Whose story is this? This is the first and most basic question a “studio reader” considers as they read a book and get a handle on what the author is doing. Besides its importance in understanding the story for its own sake, it’s also important when one is considering adapting the story for other media.

So in Dracula, whose story is it? While I was making up my own mind, I asked some “Dracula scholar” friends of mine whose story they thought it was. Some picked one particular character while others came up with the conclusion this was an ensemble story, a team effort with no one character standing out. While listening to their answers, my idea of producing a straight-forward “reader coverage” report, with a synopsis and recommendations, expanded into a more ambitious evaluation.

How would the novel Dracula stand up to a close examination using the tools of script analysis as taught by professionals who work in, as we say, “the business”? And as the discussion with my friends veered more into how Stoker’s working papers became the novel, I decided it would be interesting to approach an examination of the novel also as part of the writing process itself. What if I had been a small invisible imp on Bram Stoker’s shoulder watching him write, perhaps occasionally whispering encouraging suggestions in his ear, but most of the time just watching him get to where he needed to go by using the instincts all good writers have?

In this capacity, I’m going to offer my views on the structure behind the narrative of Dracula—my goal being not to change or “improve” his story but to discuss how he might have got to where he ended up, and why that strategy resulted in a fantastically successful novel

Melissa Stribling plays Mina in Hammer’s 1958 Horror of Dracula

Whose story is it?

While reading the novel on this most recent go-around, my reflexive conclusion was that this was Mina’s story. After all, she is an orphan, and for much of the story, she has a prominent scar on her forehead. These “Harry Potter” attributes are not likely to be wasted on anyone but the lead protagonist in a story. Yes, I’m making a joke, but I’m also quite serious. These elements are “lead character” details.

Undeterred by my reasoning, the majority of my friends answered that I was wrong and this was an ensemble story. This is an understandable perception, mainly because we are used to the main subject of a story being the most important character almost from the beginning of the first chapter. In Dracula, Stoker does the opposite—he all but hides Mina in the first part of the book. Also, the epistolary aspect of the novel invites an ensemble-like quality to the text. However, as the novel develops, the characters take on the attributes one sees in a more traditional adventure romance, where a few characters assume important roles and the rest fade into the background, even to the point where it’s hard to keep track of all the characters.

The format and nature of the text conspires to confuse the reader about whose story it is, but there is a technique to bring clarity to what is otherwise a confusing array of characters in this story.

It’s Boxing Day

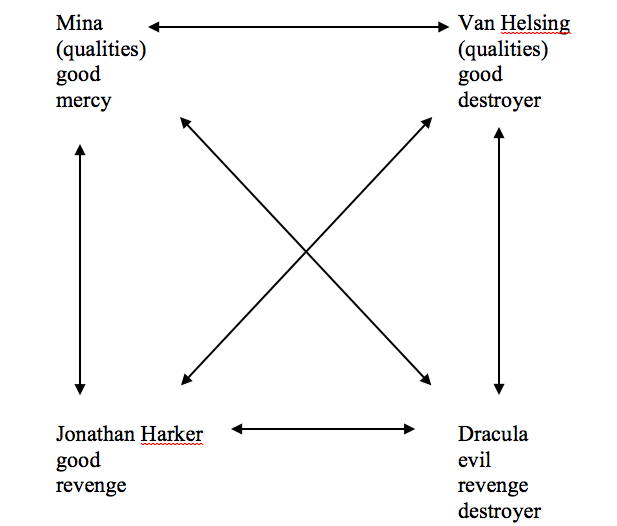

In film school, all of us had at least one class in scriptwriting, and once past memorizing Joseph Campbell’s The Hero Has a Thousand Faces, we got down to the more practical side of the business, and learned an approach to plotting called “four-corner opposition.” Visualize being in a large box, and in each corner of the box, you put: The hero, the villain, the second opponent—not necessarily the villain, but the person you are going to have a conflict with—and for the last corner you put the second opponent. Standing in for Bram Stoker, let’s see how I fill my box. The top left corner is where you put the hero, and that’s where I put Mina. The opposite corner, the villain, and—you guessed it—that’s where Dracula goes. The top right corner is Van Helsing, and the bottom left is Jonathan Harker. I’ll talk about the rest of the Crew of Light later.

Now here is where the important stuff happens. After the names are placed in their respective corners, you write down attributes of each character. The corners that are opposite should belong to the most characters most unlike each other, the characters that share the sides of the box should have some similar attributes.

So starting with Mina, the qualities I list are “good,” and ‘mercy.” Next is Van Helsing—I put “good,” “destroyer,” and “revenge.” For Jonathan Harker—I listed “good,” “revenge.” And finally Dracula—I put “evil,” “destroyer,” and “revenge.” Note that Van Helsing has a “destroyer” attribute that matches him up with Dracula, while Harker has a “revenge” attribute which also matches him up with Dracula.

The most opposite characters are Mina and Dracula, instead of being a destroyer, her first thought is of mercy. Mercy is in fact so important to Mina, she tells the Team of Light that while it is just and proper they attempt to destroy Dracula, it is even more important they use mercy in pursuit of this goal, even if it potentially brings destruction to the team. So Mina in this context is the “anti-destroyer,” the very opposite of Dracula. This suggests why Dracula is so interested in her—she is so diametrically opposed to his nature, he sees her as a valuable object to posess, and recognizes her worthiness as a foe in the fight of values that will take place in this text.

The most opposite characters are Mina and Dracula, instead of being a destroyer, her first thought is of mercy. Mercy is in fact so important to Mina, she tells the Team of Light that while it is just and proper they attempt to destroy Dracula, it is even more important they use mercy in pursuit of this goal, even if it potentially brings destruction to the team. So Mina in this context is the “anti-destroyer,” the very opposite of Dracula. This suggests why Dracula is so interested in her—she is so diametrically opposed to his nature, he sees her as a valuable object to posess, and recognizes her worthiness as a foe in the fight of values that will take place in this text.

From Stoker’s copious notes now held by the Rosenbach, it’s clear that Stoker was a plotter, not a “pantsy” (a seat-of-your-pants writer, who makes things up on the fly). While taking notes and considering storylines, it is unlikely Stoker thought: For this novel I shall use the four-corner opposition technique. Rather, this technique (or some version of it) is a natural outcome for any talented writer who meticulously outlines the plot of a story and recognizes the advantages of having characters with markedly unique traits and attributes.

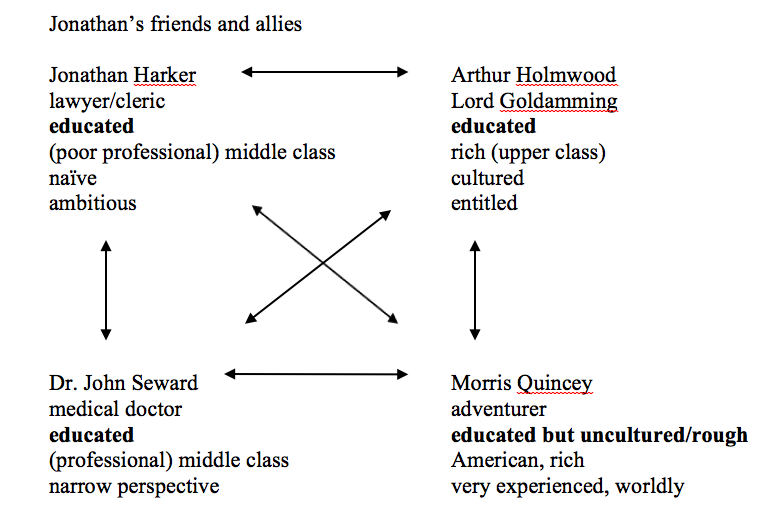

As he further outlined and fleshed out his characters, Stoker made at least some effort to differentiate the rest of his minor characters, and as a second example of creating a four-corner opposition, I am creating a box that includes four characters from the novel with Jonathan Harker at the top left side of the box (note again “opponents” don’t necessarily mean “villains”). With Harker top left, I put Arthur Holmwood top right, John Seward bottom left and Quincey in the opposite corner from Harker. Attributes for all these characters are listed in this box along with their names. I put Quincey opposite Harker as he seems the most opposite of Harker in the summation of his character, as Quincey is educated but crude & unpolished (by contrast, Harker has good social skills), quick to act (Harker is more contemplative), and rich (Harker is by comparison poor/middle class).

I created this second box to compare the secondary characters and to illustrate a point: With this visual aide, one sees that these characters have less contrast than those in the first box, and therefore are less memorable to us in the story. These are characters one is likely to have as the result of originally having an even larger number of dramatis persona, and then crossing out names, and perhaps combining one character into another. But without using four-corner opposition, it’s much harder to keep the widest amount of contrast available to the writer—instead of demanding every character remaining in the narrative to move to a corner of a room, there is a tendency to let a few of them linger, flâneur–style, somewhere in the middle, making them inherently less memorable. The use of four-corner opposition for secondary characters might not be as critical for a short or average-length novel or a screenplay, but becomes an important tool to use in a multi-episode TV or book series, which needs lots of extra characters to generate more plot.

I created this second box to compare the secondary characters and to illustrate a point: With this visual aide, one sees that these characters have less contrast than those in the first box, and therefore are less memorable to us in the story. These are characters one is likely to have as the result of originally having an even larger number of dramatis persona, and then crossing out names, and perhaps combining one character into another. But without using four-corner opposition, it’s much harder to keep the widest amount of contrast available to the writer—instead of demanding every character remaining in the narrative to move to a corner of a room, there is a tendency to let a few of them linger, flâneur–style, somewhere in the middle, making them inherently less memorable. The use of four-corner opposition for secondary characters might not be as critical for a short or average-length novel or a screenplay, but becomes an important tool to use in a multi-episode TV or book series, which needs lots of extra characters to generate more plot.

Dracula is often portrayed in films as a suave and handsome seducer, but Stoker describes Dracula as a vengeful narcissist, looking more like how John Caradine played him in Universal’s House of Dracula.

I have yet to talk about “sacrificial lambs.” Dracula leaves a long and bloody trail of bodies behind him, but there are only three significant sacrificial lambs in the story, Lucy, Renfield, and Quincey. Their purpose is to generate sympathy in the reader and to “up the ante” of the conflict, to make clear the seriousness of the situation. It’s important to understand that a narrative where everyone “skates by” and no one is significantly hurt can feel like a “cheat” to the reader who expects sacrifices and pain will happen in any conflict of true significance. The death of a sacrificial lamb we are most invested in should ideally take place near the climax of the story, which gives it the most impact. Regarding the text of Dracula, we can now recognize a weakness in the narrative structure as we feel far more sympathy with Lucy’s demise than with Quincey’s death at the end of the story.

By comparison, consider the climax of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, in which Gollum (albeit unwittingly) sacrifices himself by falling into Mount Doom, an act which ironically makes him responsible for the downfall of Sauron. For most readers, this sacrifice creates a huge “bang for the buck,” as we have become invested in his character and understand there is goodness in Gollum despite the corrosive effects of the One Ring. His death is a tragedy, but one that satisfies the reader as they recognize his presence and subsequent sacrifice ends up being the key to the success of the mission.

This sequence of sacrificial lambs, which means the character we care most about should be the last to die, does not happen in Dracula. Quincey isn’t given much to do in the story and when he is mortally wounded while helping to kill Dracula, the reader is apt to nod and simply turn the page.

How much of a flaw is this in the total picture of the book? Understanding that every novel has weaknesses and mistakes inherent in its creation, we, as readers, tend to be forgiving of missteps if the rest of the story compels our interest. As this novel has never been out of print, I would say Bram Stoker can be easily forgiven for not getting his sequence of sacrificial lambs exactly right.

To return to the examination of four-corner opposition, one can see that Mina is easily the most opposite to Dracula in character attributes. But let’s remember corner opposition is not an end in itself but is merely a useful way to visualize conflict in a story, and by looking at all the elements inside the box, one can better understand Mina and Dracula are not merely going into battle against each other, more importantly, it’s their values that are going into battle. This is going to be a contest between two value systems and setting up the four-corner opposition helps us see the nature of battle that is going to take place.

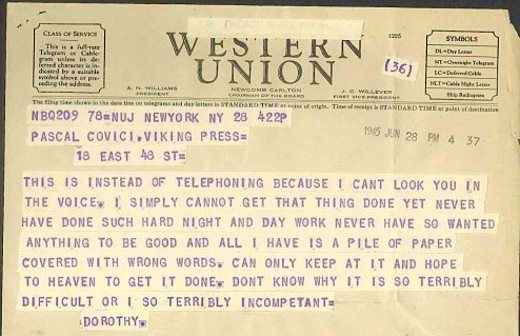

When was the last time any of us sent a telegram, if ever?

Moss Hart once said about writing a story that if you want to send a message, use Western Union. It’s a clever gag-line, but Hart didn’t mean his advice to be taken literally—what he meant was: When you are writing a story, don’t preach, or in other words, be careful not to write “on-the-nose.” When subtext becomes text, when dialogue loses either subtlety or sophistication, the audience (or the reader) will start to squirm.

Moss Hart advised writers to use Western Union when sending a message, but his plays had plenty of messages in them.

Hart was suggesting that rather than broadcasting the message of a story, one should instead smuggle it in. When finding a way to put a message into the story, usually the dialogue is asked to do the heavy lifting, as at the end of MGM’s Wizard of Oz. When the Scarecrow asks, “What did you learn, Dorothy?” the conversation appears to be about why Dorothy’s shoes will let her return home, but even this slight misdirection allows the writers to lay down the values and ideas of the film without the audience even noticing they are getting a life lesson about how and where to look for their heart’s desire.

Screenwriting teacher John Truby pulls these ideas together in his comments about writing a memorable story:

Great drama is not the product of two individuals butting heads; it is the product of the values and ideas of the individuals going into battle. Conflict of values and moral argument are both forms of moral dialogue. Conflict of values involves a fight over what people believe in. Moral argument in dialogue involves a fight over right and wrong action.

Most of the time, values come into conflict on the back of the story dialogue, because this keeps the conversation from being too obviously thematic. But if the story rises to the level of a contest between two ways of life, a head-to-head battle of values in dialogue becomes necessary.

In a head-to-head battle of values, the key is to ground the conflict on a particular course of action that the characters can fight about. But instead of focusing on the right or wrong of a particular action (moral argument), the characters fight primarily about the larger issue of what is a “good or valuable way to live.”

How does this relate to Dracula? Now that we have pushed both Mina and Dracula into their opposite corners, it is easier to see the contrast not only between the two characters, but the values they represent.

The head-to-head battle of values between Mina and Dracula can be seen in their “arguments” made to each other, either directly or by proxy to other characters. Here are the important exchanges:

Chapter 21

Dracula (to Mina): “And so you, like the others, would play your brains against mine. You would help these men to hunt me and frustrate me in my designs! You know now, and they know in part already, and will know in full before long, what it is to cross my path. They should have kept their energies for use closer to home. Whilst they played wits against me—against me who commanded nations, and intrigued for them, and fought for them, hundreds of years before they were born—I was countermining them. And you, their best beloved one, are now to me, flesh of my flesh; blood of my blood; kin of my kin; my bountiful wine-press for a while; and shall be later on my companion and my helper. You shall be avenged in turn; for not one of them but shall minister to your needs.

Chapter 23

Dracula: “You think to baffle me, you—with your pale faces all in a row, like sheep in a butcher’s. You shall be sorry yet, each one of you! You think you have left me without a place to rest; but I have more. My revenge is just begun! I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side. Your girls that you all love are mine already; and through them you and others shall yet be mine—my creatures, to do my bidding and to be my jackals when I want to feed. Bah!”

Mina: “Jonathan,” she said, and the word sounded like music on her lips it was so full of love and tenderness, “Jonathan dear, and you all my true, true friends, I want you to bear something in mind through all this dreadful time. I know that you must fight—that you must destroy even as you destroyed the false Lucy so that the true Lucy might live hereafter; but it is not a work of hate. That poor soul who has wrought all this misery is the saddest case of all. Just think what will be his joy when he, too, is destroyed in his worser part that his better part may have spiritual immortality. You must be pitiful to him, too, though it may not hold your hands from his destruction.”

When Jonathan grows angry at her request to have mercy to Dracula, Mina continues, “Oh, hush! oh, hush! in the name of the good God. Don’t say such things, Jonathan, my husband; or you will crush me with fear and horror. Just think, my dear—I have been thinking all this long, long day of it—that … perhaps … some day … I, too, may need such pity; and that some other like you—and with equal cause for anger—may deny it to me!

Chapter 25

With this argument, Mina brings up the key element of Dracula’s personality that will cause him to lose the battle—in this battle of moral argument, selflessness will always triumph over those who are selfish. Mina explains—

Then, as he is criminal he is selfish; and as his intellect is small and his action is based on selfishness, he confines himself to one purpose. That purpose is remorseless. As he fled back over the Danube, leaving his forces to be cut to pieces, so now he is intent on being safe, careless of all. So his own selfishness frees my soul somewhat from the terrible power which he acquired over me on that dreadful night. I felt it! Oh, I felt it! Thank God, for His great mercy!

We, however, are not selfish, and we believe that God is with us through all this blackness, and these many dark hours. We shall follow him; and we shall not flinch; even if we peril ourselves that we become like him.”

Mina values selflessness and mercy above all else—mercy entails forgiveness and with this act, eliminates the desire for revenge. Mina adds to this attribute an additional quality—her mercy extends to the idea that justice is still necessary but should be meted out solemnly, and without rancor, even if her friends may find themselves in danger by this course of action. We may have “boxed in” Mina, and even pushed her to a corner, yet she still thinks of the welfare of everyone else in the box, even Dracula.

Dracula, by contrast, is a man whose entire being is focused on power, subjugation, and control, and those who oppose his control are subject to his retaliation, a passion for revenge so consuming it overpowers his abilities to take more prudent courses of action that would keep him out of danger. For example, in his retreat from England, his anger of being forced to abandon his plan overpowers the more logical part of his mind that would offer options with less risk (a trip to Styria for example, and a long wait in a coffin until his trail grows cold). It is this primal selfishness that will cause his defeat and his death.

Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s comic book The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen featured a more assertive Mina

Whose story is it?

This is Mina’s story, and she will eventually battle Dracula over a basic and profound question—what is the right way to live? Should one be selfish or selfless? Dracula, with his bottomless narcissism and unremitting need for revenge, is the supremely selfish individual, and as such can only think in one dimension, or to better describe his self-absorption, he can only think centripetally, with a black hole (where his soul used to be) commanding all thought and actions around him to move toward his empty center. Dracula can buy allies (at one point he is reduced to throwing money at them) or use other forms of bribery, but this aid will only go so far, and when it fails, Dracula has meager abilities to create more complex options. In other words, Dracula is a one-trick pony, or in the spirit of the vampire genre, a “one-trick bat.”

Mina, with her proclamation that mercy is a quality more important than justice, more important than her own life, also steadfastly holds the position that grace should be given to all, even your enemies. With this winning moral argument, Mina is able to do what Dracula can never do with his allies, which is to have her friends completely invest in her cause.

Dorothy Parker sent a lot of telegrams, this one was to her agent apologizing for missing a deadline.

It is with this argument of values, and Mina’s willingness to sacrifice herself for the good of others, that in the ultimate battle, Mina defeats Dracula, sends us a message on the right way to live … and never once has to use Western Union.

Okay, so it’s Mina’s story, but… (IMPORTANT)

Some last points to make:

1) It’s helpful to know “whose story it is,” but an even more important question, after you’ve figured out whose story it is, is to ask this character, “What did you learn from this experience?” One of the most basic ways you can define a story is that it is a series of events where someone learns something, or to put in more concrete terms, it’s the Scarecrow asking at the end of the movie, “What did you learn, Dorothy?” For a character to learn something significant, it means their actions (psychologically or physically) harmed someone at the beginning of the story, and because of what they’ve learned, they are going to be a different person and not do these actions anymore. Because we don’t live in a world of villains, this harm often takes place by people who think they are doing the right thing, such as the withholding of information, or by actions that seem a minor offense or even reasonable at the time but have harmful consequences. In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s running away from home is understandable, but it shows she doesn’t trust the adults who take care of her, and her absence puts her family in great danger when the twister arrives. At the end of The Wizard of Oz, we know that Dorothy and her friends and family will still have challenges, scrapes and setbacks, like we all do, but she’s learned not to run away from her problems.

Pulling this discussion back to Dracula, Stoker’s decision to leave Mina out of the opening chapters produces a consequence to the rest of the story. Absent from the narrative, we never have a chance to see Mina demonstrate any character flaws that harm anyone. Devoid of any examples, we have to formulate our own set of flaws that Mina may have, perhaps by pulling in Lucy’s character attributes, a tendency to frivolity, not taking life events seriously, attributes one would expect most young men or women to have at their age. Having to construct our own set of flaws for Mina causes a problem with her character arc—we know where she ends up (promoting mercy and forgiveness) but we don’t really know where she started, so it’s hard to know how much “work” she really has to do to get to her “beatific” end point.

In the theater, a maxim for a playwright is: If you want to do a favor for an actor, give him a problem. The consequence of Stoker not wanting to give Mina a problem (a major character flaw) is that it means she doesn’t have a clear character arc, which gives her a certain blandness (“she starts good, and then becomes a saint”). This decision also confuses the reader as to “whose story is it?” The characters with clear character arcs (Renfield being a prime example) leave the reader with a vivid and more memorable image.

2) Why didn’t Stoker didn’t give Mina a flaw?

We are all products of our time. Stoker was writing in an era where virtuous women were likely to be put on pedestals, at least in the setting of a novel. The world was changing—for example, Flaubert’s Madame Bovary was published in 1856, but that style of writing was coming from a tradition foreign to Stoker, a British Victorian steeped in the world of stage and theater. To further remove signs of possible character flaws, Stoker does all he can to remove any hint of eroticism from Mina, displacing it to Lucy, who will become a sacrificial lamb and be punished by her ability to arouse male desire. Mina does marry Jonathan, but the event happens offstage—or I should say off-page—it is essentially a “hospital wedding” done for the convenience of getting Jonathan back to England, and even implies the possibility the marriage has not yet been consummated due to Jonathan’s illness (As an aside, this possibility was picked up by Henrik Galeen’s script for Nosferatu, which visually and through inter-titles implies Hutter and Ellen are more like sister and brother than a married couple).

Another reason to describe Mina’s character as almost faultless may have something to do with where the character herself is coming from. My impression is that Mina is a composite of Stoker’s mother, Charlotte Thornley and Stoker himself—if this is true, this might be reason enough for Stoker to think of Mina as an almost perfect woman without the hint of a flaw. This decision to make Mina’s character above reproach might have served Stoker well at the time the novel was published, but as public sentiment has changed, it potentially makes her less interesting to a contemporary audience or reader. Yet to the contemporary reader, it’s important to remember both Stoker and his audience are more than a century removed from our era—perhaps Stoker did exactly the right thing by making Mina so virtuous. After all, with the rest of the novel containing so many transgressive features, perhaps it was wise for him to make her character more traditional and familiar to the typical reader in 1897.

To recap, it may be Mina’s story, but because of the issues I’ve described, time has not been kind to keeping Mina in the forefront of the many adaptations of Dracula over the years. The good news is that the story has been done so often and already has been so radically changed, there is tremendous freedom for anyone wishing to bring their spin to what makes Mina the woman she is. As Dracula is an empty vessel able to contain whatever message or metaphor the writer wants to promote, Mina has also become a protean character able to be good or bad, angel or sinner. Like her villainous counterpart, Mina has both strength and resilience. Perhaps the greatest Mina will be in a production of Dracula that is yet to come!

P.S. If you want to know more about moral arguments in stories-

Mina may be battling a vampire, but the “deep structure” of the plot is that of a woman in conflict with a selfish man, a situation found in stories of every genre. if you are interested in learning more about this scriptwriting technique, here is a breakdown of a scene between George Bailey and the town banker, Mr. Potter in the Frank Capra film, It’s a Wonderful Life. Turns out Potter is his own form of vampire, sucking the life out of the town–here’s a link that discusses a key scene in that film.

2 thoughts on “Boxing Mina – In Search of Dracula’s Moral Argument”

Manuscript is a collective name for texts

If you mean that Stoker was a magpie for details, that certainly is true. His research in writing this novel took years and hardly a page goes by without a direct or indirect reference to a source he consulted in writing Dracula.