It was only a few minutes into watching Cold War when I started to fully recognize what I was seeing on the screen – the scene composition, the dynamic range of light and shadows – all the formal elements working together with a patter and rhythm. That’s when the thought struck me: Watching this film was like watching a long lost F.W. Murnau film.

Yet there was a lot more to this film than an elegant command of screen space. Like Murnau’s films, the characters in this story were people you cared about. Their struggles were important on a personal level, but their problems also brought the times they lived into closer focus, and in a dramatic, emotional way. How could both Murnau and Pawlikowki produce work that blended such complex emotions with such exactness of form? Then I realized what both directors had achieved this effect by showing us stories using artistic sensibilities that are not contemporary, or even recent, but rooted in ways of thinking that go back in time to the Romantic era, and perhaps even the Renaissance.

Cold War is structured as a series of tableaux, giving the sense of a dreamscape – or more accurately described as snapshots – of dramatic moments, starting in the past and moving forward, focusing on a key event and then jumping forward months or years. The story opens in the Polish countryside, 1949, and Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) is a member of a small cadre of men and women, who after the devastation of WWII, have dedicated themselves to reinvigorating native Polish song and dance. To that end, they are touring the countryside, recording folk songs and meeting prospective students. Soon a group of young men and women they have selected meet for tryouts; a chosen few will be part of a chorale ensemble that will tour Poland, with the motto that “No more will the art of the people go to waste!”

One of these potential students is the mysterious Zula (Joanna Kulig). It turns out she’s not an innocent peasant girl after all, having served a prison sentence for stabbing her father. “He mistook me for my mother, so I showed him the difference with a knife,” she explains. After belting out a Russian song from a popular movie (instead of performing a required song native to the area), Wictor disregards his fellow teachers advice and accepts her into the school. He has several reasons for accepting her into his circle – the first is that she has mammoth charisma, and though the ensemble group will be featuring folk songs from the ‘art of the people,’ extra pizazz never hurt any theatrical adventure. More importantly, the repressed and self-absorbed Wiktor, (who only shows his emotions through his virtuoso piano skills), is smitten with her beauty and her ebullient sexy voice – she’s a natural performer. Instead of the conventional student/teacher flirtations, Wiktor courts her with his piano – he’s superb, and Zula falls hard for her handsome and brooding mentor.

The choral troupe are so successful in their native music programs, they attract the unfortunate attention of Stalinist Russia apparatchiks, who waste no time in finding a way to capitalize on their music for socialist propaganda. Wiktor and his fellow teachers are told to incorporate songs patriotic to the new Soviet regime, thus torpedoing the essence of what the troupe was created to do. While no one in the cast is thrilled at turning their musical folklore into “fakelore,” some of the faculty take this decision harder than others. For Wictor the change is intolerable, and he begins to think about leaving Poland for the West.

His chance comes in 1953, when having success touring Poland, the choral troupe is scheduled to perform in Berlin, (remember that the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, until then it was an “open city,” those who wished could simply walk from one side of Berlin to the other). Wiktor plans to use this opportunity to escape with Zula, but his former student, now lover, has second thoughts. She doesn’t have Wiktor’s missionary zeal for the purity of performance, and more troubling, in Poland, she is already a name, while in France, there is no guarantee for any measure of success. On the other hand, she loves Wiktor and deeply knows he has been able to bring out her talent. Feeling conflicted and miserable (and perhaps thinking if he really loved her, he might stay), Zula intentionally misses her rendezvous with Wiktor, and follows her friends to a local bar, waiting for the awful evening to end. At the assignation point, Wictor smokes his last cigarette and resignedly leaves her behind.

For the next 10 years, the Wiktor and Zula are apart more than they are together – first by national borders and politics, and then eventually by their own flawed natures. Despite all this, they realize they have a devotion to each other so powerful that transcends any effort to explain it, except to say their love is sacred…in the sense of being inviolable, profound and eternal.

Cold War is inspired by the lives of the director’s parents, who were also named Wiktor and Zula

Cold War is based the real-life story of Palikowsky’s parents, and since they met in 1948 (as the Eastern Block closed its borders with the West) and both died in 1988 (just before the end of hostilities between the Eastern Bloc countries and Western Europe) the story of their relationship also serves as bookends for this era. In an interview, Pawlikowski explains his parents had the most dramatic and complicated relationship of anyone he has ever met, partly because they themselves were so complicated, but also because they lived in “a time when every decision you make has huge consequences, when everything has a kind of second layer of meaning.”

So what does any of this have to do with Pawlikowski and Murnau using pre-cinematic ways of thinking as a way to make bold and original films?

The answer may be found by looking first back in time to Romanticism, a cultural movement that took place in Europe before either Murnau or Palikowsky were born, but whose influence lasts even today. Murnau showed an appreciation for its ideas and beliefs in his work, and based at least one of his films (Nosferatu) in that time period. Pawlikowski also appears to have a sympathetic understanding of Romanticism, and realizing that many of the conditions that existed in Europe in the 1820s were being repeated in the 1950s, concluded that a film about his parents could be well served thematically by using the ideas of one era to help explain the other.

Pawlikowski focuses on the later years of Romanticism, when Europe entered a turbulent post-War era of uncertain borders, dislocation, poverty and political exile. Art and literature after 1815 continued the heightened emotional aesthetic present in the early Romantic era—heroism and individualism were still highly valued, along with bold action and the the “grand gesture” (a heroic act performed at great risk) but with an important addition of a fatalism, a pervasive sense that the bold idealism of the Romantic era seen early in its inception had gone horribly wrong. A sense of foreboding hangs over the many of the works from this era, reflecting a sense of doom and despondency that had replaced an earlier optimism.

Many of these conditions applied to the post-WWII era. Millions of people were dead or injured and those left were facing poverty, starvation and political uncertainty. In areas where the state or local militia could not be trusted, it was up to the individual to make decisions most likely to lead to survival. And overlying this all was a sense of sense of doom and despondency that for this part of Europe, the end of the war had gone horribly wrong.

For Pawlikowski, the story of his parent’s life is the story of bigger-than-life characters living in a larger-than-life world littered with grand themes, high emotion and great love. What better way to tell this story than to invoke the very essence of the Romantic movement itself? Let the men and women who invented “Romanticism” help tell the story of a great romance that perseveres despite great odds.

The opening scenes of Cold War will lay out these guiding principles (of evoking the Romantic) by first reproducing and visually taking us into the landscape of paintings from this era, and who better to bring into this other world than the man who many consider the greatest Romantic painter of all, Caspar David Friedrich?

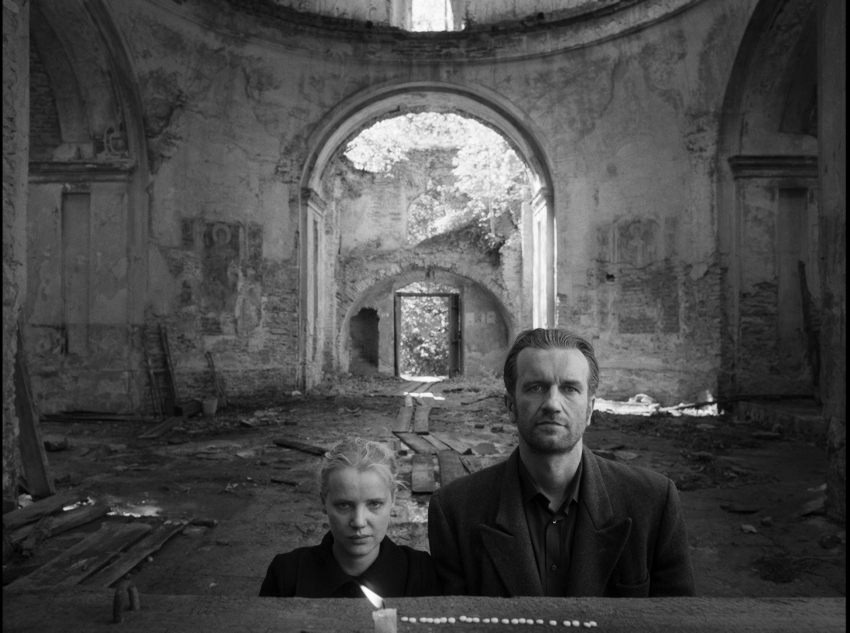

Our first exposure to this other world comes as Wictor and his colleagues stop by the ruins of a church. Having been exposed to a “sense of wonder” after recording the beautiful innocent voices of children, these men wander first around the forest, where Pawlikowski frames the branch of one tree forming an arch with another. This view of nature forming it’s own “church” (a famous and direct quotation from a Friedrich painting, “Calm in Snow”) is a visual allegory of nature becoming its own holy ground. The men then wander into the remains of a church, – it has been abandoned, and is a ruin, yet the sacred nature of the ruins is evident. It feels like we ourselves have walked into a Caspar David Friedrich painting, and to another era, which considered nature to be a more lasting and powerful representation of God (man’s work is only temporary, the divine can be seen in the forests, mountains, and stars). As if to further cement the connection of the events unfolding in the presence of divinity, as a colleague of Wiktor explores the ruins of a church next to the woods, there are a pair of eyes from a faded mural watching what goes on below, recalling The Great Gatsby’s “eyes of God,” an abandoned road sign of an oculist that the characters have to drive by when they head through the city.

Compare this mural on the church wall from the eyes from the original cover to The Great Gatsby (the artist Francis Cugat uses the idea of faceless eyes but with a feminine form, perhaps the face of Daisy)-

Along with this visual reference from Friedrich (with a side nod to F. Scott Fitzgerald), Wictor and his colleagues might as well have also wandered into a poem by William Wordsworth. Wordsworth described nature as a sanctuary from the chaos of the world around them, a place of peace and spirituality, ultimately offering a way of transition for those looking away from traditional ideas of Christianity in favor of a more personal quest for transcendence, the sacred now found through the worship of nature. As Wordsworth writes in his most famous poem, Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey:

…For I have learned

…For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.

The concept of “sacred” and its doppelgänger twin concept, the “profane” (defining one term always causes the creation of the other) was given an academic shine by French sociologist Émile Durkheim in 1912, who thought the sacred represented the unified interests of a group, which was symbolized by totems, such as the cross. The profane, by contrast, represented the worldly, unimportant affairs of individuals. Durkeim made the point that this binary pairing was the not same dichotomy as good vs. evil, and also the categories could be inherently arbitrary, the sacred in one group could be considered something evil by another, and what one group could consider sacred the other might conclude was profane.

Gabriele Paleotti (1522 – 1597) an Italian cardinal and Archbishop of Bologna.

The poets and philosophers from the Romantic era would have little to say about this modern, theoretical interpretation of the sacred and profane. Their attitudes had more in common with the views of Gabriele Paleotti, a bishop who lived in the age of the Renaissance. A lawyer by training, his skills in writing and mediation elevated him to the role of advisor to the pope, who sent him to referee ongoing disputes in the Council of Trent. Part of the bitter arguments between the Catholic clergy was the proper role and content of religious paintings, and to help set a framework for how to solve these disputes, in 1582, Paleotti wrote a book titled De sacris et profanis imaginibus (1582). In elegant, persuasive language, Gabriele Paleotti explained that the highest level of appreciating anything sacred, (a painting, a sculpture, or the heavens above us), could be obtained by studying it, not just in a sensual or thoughtful way, but in a spiritual way (he called it an “accompanying level of delight.”)

Paleotti used the metaphor of looking up at the stars in the night sky as a way to describe what he meant. The first level of delight, he explained, is through the senses, to simply pay attention, see the stars twinkle, and marvel at their existence. The second, deeper level of delight was to study the stars is in the way of a scholar, to understand the glory of their movement in the sky and their relationship to each other. The last and most “sacred” level of delight was to connect to it in not just an emotional and intellectual way, but have such a level of attention and devotion to the heavens that they receive divine inspiration (Paleotti called it receiving “supernatural knowledge”). When this third level of delight is achieved, they would have access to the bliss that only the Heavenly Father can give.

Three hundred years later, the Romantics would borrow many of these ideas and infuse them into their precepts of a new way of thinking about the world. In particular, Romantics emphasized nature as a way to access these spiritual “levels of delight,” indeed, a deeper understanding of our place in nature was used by the Romantics such as Wordsworth in their efforts to pull away from Christian dogma and create a more secular space for ideas of spirituality.

Just because Pawlikowski uses the ideas of the Romantic era doesn’t mean he is a captive to that time, especially when subsequent ideas and movements bring up ways to think of Romanticism in a new light, or to use a musical comparison, use the ideas of the Romantic era, but in a different key. Expressionism was a movement in Germany with many romantic components – so many that critics have argued Expressionism is just a modern version of the Romantic movement. Murnau used components of Expressionism in much of his work, and Pawlikowski references Expressionism in Cold War with his photography, using low-key lighting and high contrast, by doing so, he pulls in 20th century stylistic devices that fit inside the larger rubric of Romanticism. In fact, he goes out of his way to reference film noir, a genre that was arguably created from the same kind of impulses of romanticism that fuel much of the story we are watching. He does this is by including a scene in Paris where Wictor is working a “day job” by helping to score a film. While recording music in a studio, matching music to a scene from the film projected on a wall in the studio, the image of an archetypal noirish menacing figure crosses the screen.

At this point Zula bursts in the studio door, ruining the take. Wictor’s anger at her action quickly disappears as she has important news to tell him, and the film he is working on is quickly forgotten. The scene plays as an inside joke, Pawlikowski is telling us that Wictor has no time to waste on an art form that packages emotions and impulses into an easier-to-digest genre narrative because he is actually living in his own “film,” one with a more complex story. In other words, Wictor doesn’t have time to artistically take part in the making of a film, he’s too busy creating his own, personal narrative.

Pawlikowski uses music throughout Cold War to chart the emotional status of both the time and location of the scene, and in particular the status of Wictor and Zula’s relationship. While Murnau used paintings as a way to reference and to then repeat a particular theme throughout the film as a visual leitmotif, Pawlikowski use the idea of leitmotifs in their original musical sense, as ways to describe to describe each character and to chart their progress in the story. For example, he uses the same songs played in different styles and tempos throughout the film, and these songs give us an intuitive understanding of where the lovers are in respect to each other and to their surroundings.

Wictor and Zula are on a quest, but what are they after? I would argue they are both in a search for communion with the sacred, and for them, the sacred can be found in music. Using the metaphor of the three levels of delight supplied by Paleotti, the first level first meeting (when she tries out for the school), there is of course, the initial physical attraction for each other. The second, deeper level of delight occurs when the two study together; Zula sees that Wiktor plays the piano not just well, but beautifully. Wiktor sees that behind Zula’s lack of knowledge of the folk traditions, there is something hauntingly original in her voice that captures the authenticity of what he is seeking. At some point, with music being their own “language of the heavens,” the lovers reach a bond, a communion that I would describe as an understanding and devotion to each other, that transcends the physical barriers of their world, and eventually their own shortcomings.

Pawlikowski uses this music as a way to expose us what is the hearts of Wictor and Zula. For example, by following the course of one song in this film “Dwa serduszka” (Two Hearts), one can track the spiritual journey of this couple. We hear the song four times, first a “naïve” folk song version in Poland, the second time sung by Zula with a jazz piano improvisation by Wiktor in a Parisian club, then as a “torch song” sung by Zula, and finally as a French “chanson” (retitled “Deux Coeurs”) on an album Wictor is producing for Zula. Following the journey of this one song in its four versions is to follow the journey of Wictor and Zula, their journey from the sacred to the profane, and by extension, the challenge we all have to stay true to what inspires us.

The sacred they have found with each other, but the profane will attack them from every corner. The profane can be anything that prevents us from what we treasure and value, in the case of Wiktor and Zula, it includes geography, politics, ambition, even their own emotional frailties.

To understand this better, it is helpful to be very specific as to what happens with the last time we hear this song. Near the end of the story, Zula, who has married an Italian man just to get out of Poland, finally arrives in Paris, ready to renew the romance. But she has changed and so has Wiktor who is now making his living by playing in jazz clubs. They decide to cut a record, with Wiktor as her producer. But now they are far removed from the achingly beautiful innocence of Polish folk songs, instead she is singing music with a phrasing and melody alien to who she is and where she’s from.

To understand this better, it is helpful to be very specific as to what happens with the last time we hear this song. Near the end of the story, Zula, who has married an Italian man just to get out of Poland, finally arrives in Paris, ready to renew the romance. But she has changed and so has Wiktor who is now making his living by playing in jazz clubs. They decide to cut a record, with Wiktor as her producer. But now they are far removed from the achingly beautiful innocence of Polish folk songs, instead she is singing music with a phrasing and melody alien to who she is and where she’s from.

Wiktor stops the recording again and again, reminding her of her task of being a Parisian chanteuse. The session is completed, a record pressed, and as Zula holds the album in her hand, she realizes what is inside is not her, her soaring and ethereal voice has been bridled, packaged, objectified…reduced to a commodity. She thought that an escape to the West from the Eastern Bloc would give her freedom, but as Zula thinks back to her time in Paris—the signs, the branding, the  commercialism—she realizes the problem, perhaps even the evil, behind the politics and ideology of both Communism and Capitalism: Both systems have an endless need to objectify and commodity—to reduce people to objects that can be manipulated. In other words, both systems have an endless need to find the sacred and make it profane. She abandons Wiktor to return to Poland, and then it is time for Wiktor (in the best Romantic Era style) to make another grand gesture.

commercialism—she realizes the problem, perhaps even the evil, behind the politics and ideology of both Communism and Capitalism: Both systems have an endless need to objectify and commodity—to reduce people to objects that can be manipulated. In other words, both systems have an endless need to find the sacred and make it profane. She abandons Wiktor to return to Poland, and then it is time for Wiktor (in the best Romantic Era style) to make another grand gesture.

In the end, their devotion to each other will be all they have left. The film closes with Wiktor and Zula returning to the ruins of the church seen at the beginning of the story. The washed-out mural of the “eyes of God” watches the couple enter and then approach the altar.

Wiktor and Zula give marriage vows to each other, and never has a ceremony been more sacred. In the ruins of an abandoned church, a piece of earth that no one has found any value, they embrace, for they have found their last refuge.

List of sources referenced:

There are many excellent interviews with Pawlikowski available, Vulture has two articles, this one specifically details the songs used in the movie-

https://www.vulture.com/2018/12/the-stories-behind-the-songs-in-cold-war.html

Roger Ebert.com has two articles about Cold War, a review by Tomris Laffly, and with another interview, with additional information about his parents-

https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/melancholy-optimist-pawe-pawlikowski-on-cold-war

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/cold-war-2018

This article in the Atlantic by Rachel Donadio details the cultural complexities of Cold War as the film relates to present-day Poland-

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/12/pawel-pawlikowskis-cold-war-love-despite-conflict/578689/

An excellent resource on Gabriele Paleotti with an English text can be found here-

https://shop.getty.edu/products/discourse-on-sacred-and-profane-images-978-1606061169

Paleotti’s discussion of the “hierarchy of delights” can be found in “Art Theory as Ideology: Gabriele Paleotti’s Hierarchical Notion of Painting’s Universality and Reception,” by Pamela Jones. Click here for more information-