If there is one name associated with children’s entertainment, that name is Walt Disney. The word “Disney” is many things to many people: a man’s name, a legend, a label, an icon, a construct, a complement, a criticism, a blue-chip stock, a radio station, a television network, a theme park, a career for thousands, a multinational corporation. The name of Disney is so much part of our culture that it is hard to imagine a world without the name and all the meanings it implies. In short, Disney is an empire, an empire built with one foremost goal: to please a child.

Yet Walt Disney was not the first man with this dream.

“To please a child” was the purpose of an earlier American dreamer, schemer and entrepreneur, L. Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and many other children’s books. In 1914, Frank Baum was also president of a well-funded, ambitious Hollywood film studio. Its goal was to be the first studio in the world to produce quality films for children. If not for the vagaries of chance and mistake, another empire might have taken the role now secured by Disney. Instead of taking vacations to Disneyland, we might all be going to—Oz.

Apart from the famous MGM movie (how many have you seen it, and how many times?) and a score of occasionally read books, we don’t go to Oz on our summer vacations. What happened to Baum’s dream of making an industry from his creations? Why did Baum fail so completely at his attempt at empire, while Disney succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest imagination?

One hundred years ago, L. Frank Baum was the preeminent children’s book writer in America. Baum first caught the public eye with a book titled Father Goose, but this success was soon eclipsed by The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a clever reworking of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. William Leach, in his article, “The Clown from Syracuse” points out that a century ago America was experiencing a pivotal change in religious thinking.

This radical religious repositioning had many names: theosophy, New Thought, the “mind-cure.” The details differed, but the important point was that all these religious impulses reflected a decline of traditional American Protestantism, and its accompanying doctrines of sin and guilt. The “scarcity” philosophy of thrift and hard work may have made sense in the hardscrabble lives of farmers, but America was now full tilt into the Gilded Age. A new abundance of products, and the money to buy them, made traditional values, such as thrift, seem obsolete. In Oz, as in America in 1900, it was no longer as significant to build character as it was to acquire the right personality. It may have been important for Dorothy to be a good girl, but it was more important for her to wear the right shoes.

Following the success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum was persuaded to have the book adapted to the stage. The job of adapting the book was given to veteran producer and director Julian Mitchell, who saw the potential of the many colorful characters and spectacular scenes. He also saw the drawback to the property—that it was mainly for children. Mitchell overhauled the Wizard of Oz concept, bringing in romantic love interests such as Tryxie Tryfle and allowed plenty of opportunity for the chorus of women playing guards and soldiers to show off their shapely ankles.

Mitchell essentially turned the production into a musical review, an excuse for a series of sketches and songs, such as “Hurrah for Baffin’s Bay,” and “When You Love, Love, Love.” The idea that songs in a musical needed to do “double-duty,” that is, be enjoyable songs but also advance the story, was years away. Whatever its shortcomings to modern eyes, the original musical stage version of The Wizard of Oz was a tremendous success, running for a total of 11 years, and was probably the inspiration for MGM turning the story into a musical in 1939.

Never a man to stand still, in 1908, Frank Baum developed a production he called “Fairylogue and Radio-Plays.” This time, the conception and details of the show were all Baum’s. Frank Baum played ringmaster in a touring show that combined lecture, slides, film clips, and a live orchestra. Baum would start by speaking to the audience, and then he would run films and show slides of characters from the Land of Oz. One can see an effort on his part to “take back” Oz from its stage musical alterations, and return Oz to the children for which it was originally intended.

The combination of these elements, in what today would be called a multimedia presentation, seems audacious even by today’s standards and illustrates how imaginative Baum was in his approach to the entertainment world. The reviews of this show were excellent, but the production lost money. For the first time, Baum was forced to face the downside to targeting children—the traveling show was constructed for matinees, and lower children’s prices made the expensive mechanics of the production impractical. By catering to children, the theaters could not charge the full ticket prices, and the show could not make a profit. Baum was forced to stop touring, and lost his investment. In only eight years, Oz had carried Baum from rags to riches and back to rags.

Taking his bankruptcy in stride, Baum kept writing books and plays, gradually getting out of debt. As part of the bankruptcy agreement, a Hollywood producer William Selig received rights to film Oz stories. Selig released the first filmed version of The Wizard of Oz in 1910. Other than supplying the story itself, Baum had nothing to do with the production.

A one-reel film of only about twelve minutes, this first filmed Wizard of Oz met with an indifferent reception by the audience and was soon forgotten. Today, this film is housed in the Eastman House film archives in Rochester, New York.

The same year, 1910, Baum relocated to Hollywood, California. Initially moving for health reasons, Baum quickly became friends with men who were part of the fledgling movie industry growing up in Los Angeles. In 1914, members of the Los Angeles Athletic Club announced the formation of a new company, the Oz Film Manufacturing Company. The company was incorporated, and $100,000 of stock sold in just ten days. The company had high hopes. This is from a promotional flyer:

“Oz films are distinctive. Nor rehash of worn-out plays, inane magazine stories or discarded novels, but ORIGINAL creations of World’s Greatest Author of Fairy Tales, L. Frank Baum, who has infused Oz films with the rich, red blood of his imaginative genius.”

Thirty years later, writing for the magazine Films in Review, Frank Baum, Jr, described the building of the Oz Manufacturing Company studio. Seven acres of land was bought in an area of town next to Santa Monica Boulevard, making this one of the largest studios in town. An enclosed stage, 65’ x 100’ was designed by Baum and erected. Underneath the grounds, running a full length of the stage, was a concrete tunnel, a large concrete tank, and eight smaller tanks, all of which could be used to make lakes or rivers. A company of players could disappear through trap doors on the stage and into the tunnel, making large-scale transformations possible.

Oz studios did not lack for amenities: dressing rooms, hot and cold baths, call bells, settees in place for the actors. One building was constructed so that background sets could be designed in one piece. Another building was constructed so that the film could be processed on the premises.

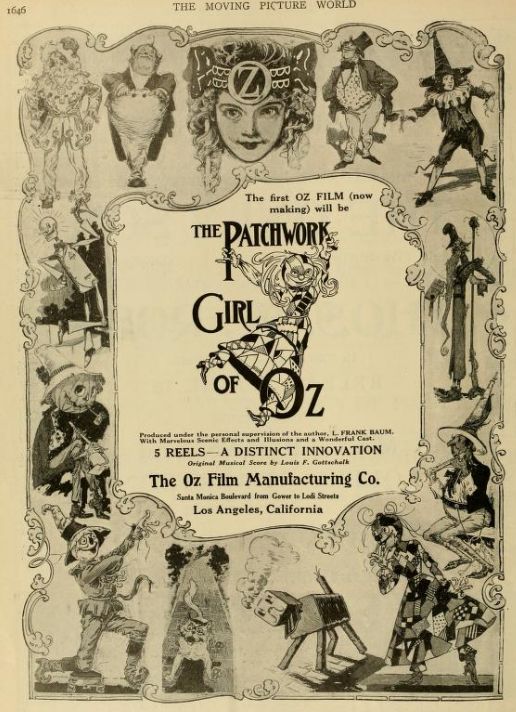

In 1914, filming began on The Patchwork Girl of Oz, the story taken from one of the many sequel books to the original Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The title role of the Patchwork Girl fell to a French acrobat named Pierre Courderc and J. Farrel MacDonald directed the film. Five reels long, The Patchwork Girl of Oz premiered in the gymnasium at the Los Angeles Athletic club in July 1914.

The Oz Manufacturing Company then ran into its first real problem—distribution. In 1914, it was possibly easier to make a film than to get it to be seen. Theaters at the time were signed to long-term contracts, not allowing them to show features from independent companies. The only way Oz Manufacturing could distribute their film was through another an existing studio, which had little interest in giving up valuable theater time to show off someone else’s product. To make matters worse, Oz Manufacturing (along with other studios) was sued by the Motion Picture Patents Company over claims that the company was violating patent laws.

Oz Manufacturing paid off the Edison lawyers in a settlement, and finally reached an agreement with Paramount for distribution of their films. Brushing aside these major hurdles, the studio continued work on its second film, His Majesty, The Scarecrow of Oz. The Land of Oz was open for business and bustling with action.

It was this precise moment when activity in the Oz Manufacturing Company suddenly came to a halt, or to use an Ozian metaphor, a cloudburst of rain caught the studio like the Tin Woodman, freezing it in midchop.

The Patchwork Girl of Oz, to put it bluntly, bombed. Worse than just producing low attendance at the theaters, it provoked negative reaction from the customers, angry patrons demanding their money back for a ‘kid movie.’ And a film targeted for children meant lower ticket prices for its entire run, which made no sense to theater owners struggling for every penny. The Patchwork Girl of Oz was a huge loss of income for the theater owners, and Paramount, burned by a product that wasn’t even their own movie, refused to distribute His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz.

Oz Manufacturing now had two feature films and nowhere to show them. Scrambling, they cut deals around the country. In the second Oz film, His Majesty the Scarecrow of Oz, Baum had gone back to the basics of what made the original book and stage musical so successful, namely Dorothy, the Scarecrow and the Tinman. The results produced a far better film, but now it was too late. The Patchwork Girl had acquired such a negative reputation no one was interested in more stories from Oz, and His Majesty, The Scarecrow of Oz was never properly distributed or promoted. At December of 1914, Oz Manufacturing finished its last Oz film, The Magic Cloak of Oz, but had nowhere to show it. Oz Company was eventually forced cut these features down to two reel fillers. Whatever money they eventually got back in no way covered the enormous costs incurred in setting up the studio earlier in the year.

Frank Baum and his friends had made major mistakes but they were not stupid. Seeing their hope of making children’s movies dashed, Baum and his friends revamped the concept of the studio, changing its name to Dramatic Features Company. Bowing to the necessity of filming adult stories. Baum wrote screenplays for films including The Gray Nun of Belgium, a war story, and a romance, The Last Egyptian. It was no use. Anything from what formerly had been Oz studio smacked of child’s entertainment, and thus, box office poison. Having no way to show their films, Dramatic Features, AKA Oz Manufacturing Company went down like a witch after being dunked with a bucket of water. With mounting debts, and no virtually no income, the studio declared bankruptcy, losing its charter and lease in 1915.

Four years later, L. Frank Baum would die of a heart condition and a stroke. While his reputation as a writer of children’s books was secure, Frank Baum’s adventure into the world of movies became merely a footnote in Hollywood history.

Four years later, in 1923, a young commercial artist from Kansas City arrived in Los Angeles full of dreams and visions. With his brother Roy, this energetic young man, Walt Disney, produced a series of short films combing animation with live action. Then Walt made, with fellow artist Ub Iwerks, a series of cartoons, eventually starring a character named Mickey, which proved to be a hit. In 1933, Walt Disney released a short cartoon, The Three Little Pigs, which was an enormous success. Using his profits from The Three Little Pigs, in 1937 Walt released the first full-length animated feature, Snow White, and was on his way to empire.

Why did Walt Disney succeed while Frank Baum failed? Some answers are obvious. The Oz Manufacturing Company was set up backwards. The initial large sums of money should have first gone to settle distribution issues, and the hot and cold running baths could have waited until their after the first big hit. Many of Oz Company’s troubles were reflected by the grandiosity and arrogance of the way it was founded.

Baum was also fighting age and his own mortality. Frank Baum was 58 when he became president of the Oz Manufacturing Company, not perhaps too old an age for success, but with no time for failure. When Walt Disney started his career in Los Angeles he was 22, with abundant time to experiment and learn from his mistakes. By persistence, and an obsessive attention to detail, Disney studios grew from a ‘garage start-up’ company to an animation studio that became the industry standard.

Still, there are more subtle answers. Walt Disney succeeded because Disney was not just the name of a man, but the name of two men, Roy and Walt Disney, brothers. The brother act was a team effort: good cop/bad cop, comic/straight man. Walt had the ideas, and his brother Roy handled the unglamorous but essential business end of things. Roy may have felt justly neglected by his brother as the company grew, but he was always loyal, and anyone who researches the success of Disney quickly sees that Roy played a vital role in Disney’s success. For his film efforts, Frank Baum never enjoyed the partnership of a person who could fill the role of a Roy Disney.

Another reason Baum failed was his lack of critical distance to his own work. It was a mistake to put Frank Baum in charge of production. For example, with hindsight, it was an obvious blunder to go with The Patchwork Girl of Oz as their first film. American audiences did not know or care about a Patchwork Girl. They wanted to see Dorothy Gale from Kansas.

Dorothy was a simple Kansas farm girl, whose only thought after the Wicked Witch melted was to pour more water on the floor and clean up the mess. Like many authors who create a character that assumes too much power, perhaps Frank Baum was both tired and a little jealous of Dorothy. It might have given Baum great satisfaction to have pushed her over the Reichenbach falls to meet an end like another character grown too big for his britches, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. With critical distance on his own work impossible, having Baum, both president, creative head of development, AND head writer of the studio, was setting up the company for failure before it ever started.

By comparison, Walt Disney was never interested in being a famous author, spending much of his career adapting other people’s ideas and finding innovative ways to adapt these stories to the screen. In other words, Disney’s skills were more of an editor than an author. In terms of story development, this attribute was priceless—his vision of what in a story was needed and what should be left out gave Disney an amazing track record of success. This insight would hardly have been possible if Walt had been working with his own material.

Luck was vital for both men. Baum entered the film business competing with larger companies who had already formed distribution contracts with theaters, in that sense he was late to the game, but more importantly, his business model of making films for children was attempting to reach a market where there was not yet a clear demand. Five years later, this market began to grow and by 1937, Disney made Snow White, and never looked back.

In 1914, there was one final insurmountable problem—no color film in the sense we think of it today. True, there were approximations, with tints and tones used to specify light conditions, and hand painting available for short films. These efforts have their own beauty but were simply unable to capture the real essence of Oz. As I think any reader of the novels would agree, color is essential and indispensable to The Wizard of Oz. Every page is splashed with color, from the wonderful drawings by Art déco illustrator William Denslow, to the vivid written descriptions of the Land of Oz given by Baum himself.

Without color, Oz is just not Oz, and this was a problem beyond Frank Baum’s ability to solve. Twenty-five years later, Dorothy, played by Judy Garland, stepped out of her drab black-and-white world into a world of dazzling Technicolor, and Oz had arrived.

Another reason why Baum failed was his lack of critical distance to his own work. It was a mistake to put Frank Baum in charge of production. For example, with hindsight, it was an obvious blunder to go with The Patchwork Girl of Oz as their first film. American audiences did not know or care about a Patchwork Girl. They wanted to see Dorothy Gale from Kansas.

Dorothy was a simple Kansas farm girl, whose only thought after the Wicked Witch melted was to pour more water on the floor and clean up the mess. Like many authors who create a character that assumes too much power, perhaps Frank Baum was both tired and a little jealous of Dorothy. If he could, I think he would have pushed her over the Reichenbach falls to meet an end like another character grown too big for his britches, Sherlock Holmes. With critical distance on his own work impossible, having Baum both president and head writer of the studio was setting up the company for failure before it ever started.

Walt, on the other hand, spent most of career adapting other people’s work for the screen. Never claiming to be an author, Walt Disney had other qualifications such as imagination and salesmanship, and he had an even more important quality—he could be ruthless. This did not always make him friends in the business, but in terms of story development, this attribute was priceless—his vision of what in a story was needed and what should be left out gave Disney an amazing track record of success. This insight would hardly have been possible if Walt had been working with his own material.

Luck was vital for both men. Baum entered the film business too late to easily form distribution contracts with theaters, but too soon to market children’s films where there was not yet a clear demand. Five years later, that market began to grow. By 1937, Disney made Snow White, and never looked back.

In 1914, there was one final insurmountable problem—no color film. True, there were approximations, with tints and tones used to specify light conditions, and hand painting available for short films. These efforts have their own beauty but were a pale imitation to capturing any real essence of Oz. As I think any reader would agree, color is essential and indispensable to The Wizard of Oz. Every page is splashed with color, from the wonderful drawings by Art Deco illustrator William Denslow, to the vivid written descriptions of the Land of Oz given by Baum himself.

Without color, Oz is just not Oz, and this was a problem beyond Frank Baum’s ability to solve. Twenty-five years later, Dorothy, played by Judy Garland, stepped out of her drab black-and-white world into a world of dazzling Technicolor, and Oz had arrived.

A version of this article was first published in The Nassau Review

Bibliography

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, edited by William Leach, including “The Clown from Syracuse: The Life and Times of L. Frank Baum” and “A Trickster’s Tale: L. Frank Baum’s Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” (both by William Leach) Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing, 1991.

“The Oz Film Company,” by Frank Joslyn Baum. Films in Review, vol. 8 August-Sept. 1956, pages 329-333.

Oz Before the Rainbow, by Mark Evans Swartz. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000, pages 192-196.

“Doings in Los Angeles,” Moving Picture World, 18 April, 1914. 348.

The Oz Scrapbook, by David Greene and Dick Martin. New York: Random House, 1967, pages 142-154.

One thought on “The Man Who Would Be Disney”

Excellent! More, please!