Ukraine has been getting a lot attention lately and those interested in its culture may be surprised to find out it had a robust (if brief) silent film history. After the overthrow of the Russian monarchy by a revolution in 1917, there was a six-year battle between the Red Army, led by Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik Socialist forces and the White Army, a coalition of forces that favored political monarchism. At the conclusion of the war, which saw as many as 12 million people killed (many of them civilians and non-combatants) the war was decided in favor of the communists, and Ukraine was given a reasonable amount of autonomy within the sphere of the Soviet Union.

With this freedom, the All-Ukranian Photo Cinema Adminstration (VUFKU) was founded, with two studios, one in Odessa, and the other in Kyiv. These studios—far away from Moscow—operated with relative autonomy from 1922 to 1930 and produced hundreds of short subjects and at least 33 features films.

One of these films was Two Days (Dva Dnya, 1927). Directed by Georgiy Stabovoy, the film is set during the 1917-1921 civil war in Ukraine and recounts two days in the life of Anton (Ivan Zamychkovskyi), a faithful doorkeeper of a family with a rich estate. When the family flees from the advancing Bolshevik troops, the faithful servant Anton stays behind to guard the valuables buried in the garden.

During the hasty escape, Sergey, the young son of the estate owner, is separated from his family and in desperation returns to the estate. Anton, knowing the Bolsheviks might kill him if they find out his identity, hides him in the attic.

The Bolshevik Red Army arrives and converts the house into barracks for their men. Anton is surprised to see that the leader of the Bolsheviks is his own son, Andrii, who had joined the Red Army earlier in the war. Anton, whose only loyalty is toward his employer, the master of the estate, and who is sheltering the son , is forced into an uneasy truce with his estranged son.

This truce falls apart when the boy sees Andrii discover the buried family valuables in the garden, and after a hard-fought battle, the Whites regain the ground they have lost, and take back the city and the estate from the Red Army. With the White Army back in control of the land where the estate is located, Sergey discloses to an informer that Andrii is a Bolshevik and despite Anton’s pleas and protests, he is shot by a firing squad.

Watching his son die forces Anton to realize his efforts to avoid taking sides in the war has failed. By not taking any position, and by only showing human kindness to the estate owner’s family, he has lost what mattered to him most, his son. His conclusion? Whether he wanted to, or not, he is now part of the fight. His efforts to remain a non-combatant has been rendered irrelevant by the events around him. Now he must take a stand and choose a side, and with nothing left to loose, he sets the house on fire, along with the White Army generals who are partying inside.

Two Days is an eye-opening view into a world of Soviet silent cinema that rarely gets attention from film festival programs interested only in a short list of “greatest hits” like Potemkin and Earth.Two Days forcefully makes the point that in this era, the film studios in the communist countries were not monolithic propaganda machines where capitalist villains invariably met defeat against Soviet proletarian heroes, but instead had the ability to produce nuanced stories that allowed for various points of view. In particular, Two Days examines the terrible dilemma civilians face when placed between two armies. We all know that war is dehumanizing for the participants in the battle, but this film emphasizes that a special burden falls to the civilians who essentially become untrained and unarmed combatants in a struggle they often want no part of. The actor who plays the doorman, Ivan Zamychkovskyi, is especially effective as his role of a loyal doorman who must struggle over the issue of shifting loyalties, and his performance reminds me of Emil Jannings, who essayed similar roles in his career.

Contemporary reviews noted the excellent acting and compelling drama of this film and it received distribution abroad, screening in other European cities. It’s important to note that Two Days was the first Ukrainian film to be distributed in the United States.

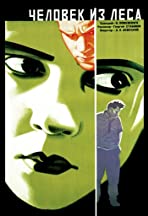

Another film directed by Georgiy Stabovoy was THE MAN IN THE FOREST (1927)

By 1926, VUFKU, the All-Ukranian Photo Cinema Adminstration, had become a productive organization, with the number of its films being released in Germany secondary only to the United States. By 1929, its market had extended to as far as Japan.

But dark days were ahead. Stalin, who had assumed leadership of the Soviet Union after Lenin’s death in 1924, gradually consolidated his power, and by 1930 he had begun a system of cultural suppression and increased state collectivism. One major focus of this suppression was Ukraine, which had vast natural and agricultural resources. VUFKU was disbanded and its stable of artists were brought under suspicion. Fellow Ukrainian director Olexandr Dovzhenko, famous for films such as Earth, was spared by Stalin, who had seen one of Dovzhenko’s prior films, Arsenal, and liked it. But the rest of the VUFKU filmmakers were not so lucky. The clearly talented director of Two Days, Georgiy Stabovoy made four more films but by 1930, his career was ended. Two Days director of photography, Demutskyi, was accused of sabotage, and sent to Central Asia. Producer Mykola Khvyliovyi, one of the prime advocates of allowing artistic freedoms to Ukrainian filmmakers in a setting far from Moscow, after undergoing intense pressure from Soviet investigators, committed suicide in 1933.

Stalin’s efforts at suppression met with a temporary success, which he expanded to the Soviet Union as a whole, culminating in the Great Purge, also called the “Great Terror,” where by 1939, hundreds of thousands of people were executed and at least a million people were sent to labor camps.

The result of this suppression was a vast and pervasive cultural amnesia. Ukraine was especially hard hit.

Two Days suffered the fate of almost all the other Ukranian films made in this period, the fate of being forgotten. By 1932 it was given the label of a “petty bourgeois” film and disappeared from the collective consciousness of both audiences and film libraries—it was all but unknown until a 2011 restoration by the Dovzhenko National Film Centre.

In his efforts to control the Soviet Union, born out of the ashes of the Russian Empire, Stalin concluded that cinema’s natural ability to formulate and promote dissent was important to restrict and suppress. For Stalin, the independent spirit obvious in films coming from Ukraine were a perfect example of why this subjugation had to be complete and total.

But if Stalin ever saw Two Days, he was oblivious to its message. At the end of the film, Anton is forced to pick sides and having chosen, strikes at the enemy in his own way by setting fire to his landlord’s house, the house he originally tried so hard to protect. Anton’s act dramatically illustrates that any attempt to suppress dissent will create a response in kind, and these actions can escalate to an outcome where no one may be the winner but there will be definite losers. With his Great Purge, Stalin was creating a generation of Russians who lost faith with the revolution, and by that act, was laying the seeds for the eventual future collapse of the Soviet Union.

And today, with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, this pattern is repeating.

The homes in Ukraine may be indeed burning, but in a larger sense, what we are seeing is the burning down of the Russian Federation. Putin is creating a million Antons, none of whom will want to live in a house that Putin built.

6 thoughts on “Burning Down the House: The Ukrainian film Two Days (1927)”

To be able to view these films would be great!

And…I feel so fortunate to know (kind of) a dracula scholar! 😁

You can access this film by various means. There was a DVD set of Ukrainian cinema in which this film was included but I don’t see any websites that currently sell this item, at least in the U.S. You can use the German words for “Two Days” and find a version on youtube that has English subtitles, I don’t know if this is the original version or a version that was released in 1932 with a soundtrack. I also think it is available on MUBI. Good luck!

Thank you! Will be on the hunt.

I have investigated the question of whether or not it is possible (to currently) watch Two Days in the States. It apparently WAS on MUBI but they have removed it. It was available on DVD as part of a boxed set of Ukrainian silent film, which was released in 2011, but when I looked further, it was released from the Ukrainian Film Center itself! In other words, unless a supply is available from some other source, you would have to get a copy mailed to you from Ukraine. They might be happy to hear from you, they might not, I don’t know. Here is a link to a great book they put out about Ukrainian silent film-

https://issuu.com/dovzhenkocentre/docs/ukrainian_silent

Fascinating. Ukraine’s independent temperament is longstanding, as is their resourcefulness, talent, and skill. That their films were briefly second only to America’s as German imports is remarkable. So the indomitable spirit that is galvanizing the world today is not new, which is amazing enough, but their resiliency, getting up after each devastation and once again fighting to become a vibrant country, is maybe even more amazing. Thanks for this, Lokke, most illuminating, most illuminating!

Thank you! From looking at the history of the country, in particular the flowering of art and culture in the 1920s when they were mostly left alone, I think the major reason for the current invasion is not agricultural or geopolitical, but the basic fact that Ukraine was starting to thrive with a open-market “Western” approach, and that was making their neighbor to the east very, very nervous.They have culturally considered Ukraine to be their “backward brother” that needed help (code word for control and domination) so that Ukraine’s recent successes are a huge blow to that mindset.