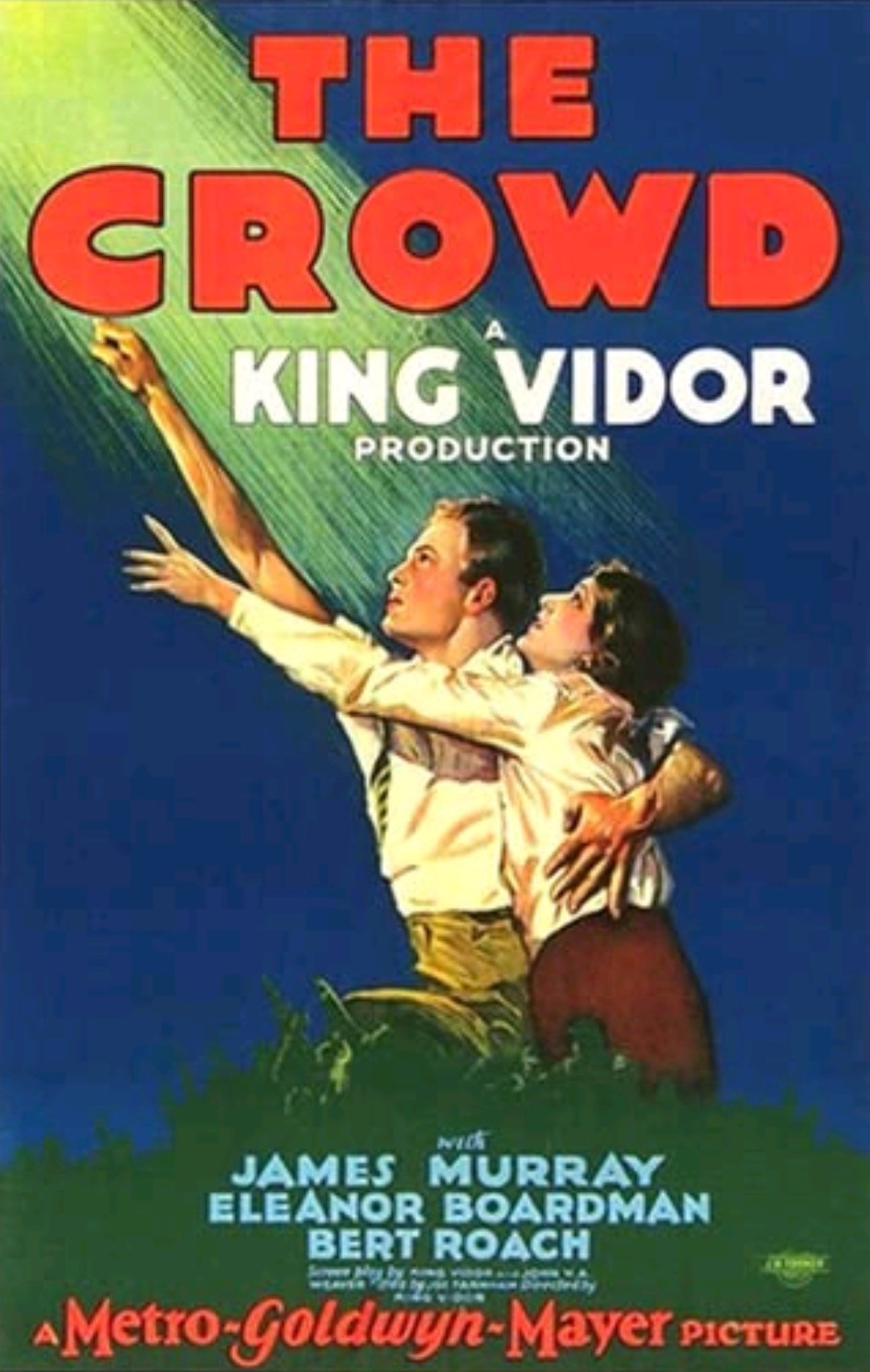

Everyone has their own choice for the best silent film ever made, my choice is King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928), which I saw most recently in a special screening attended by Kevin Brownlow and with a live orchestral score by Carl Davis, who was present to conduct his own music.

The premise of The Crowd is simple: It’s the story of a man named John Sims, born on the Fourth of July, 1900. Twelve years later, John’s father dies but not before he has drilled into his son the need for him to be better than everybody else — to be important, to stand out from the crowd. At the age of 21, John sets out for New York City, gets a job at an insurance company, then meets and falls in love with a woman, Mary (Eleanor Boardman). They marry and raise a family. John has the normal strengths and failings we all have but one thing he has an extra helping of (courtesy of his dad) is ambition. As life’s disappointments mount, he nurses his ambition and pride as best he can, burying it deep inside of himself. Worse, he feels ashamed that he’s just one of ‘the mob’ and this isolates him from his wife and children. And when tragedy strikes the family, John’s pride comes roaring back, this time wrapped in the disguise of feeling sorry for himself — John loses his job and becomes a vagrant. Mary, long loyal to her husband, is persuaded to end the marriage. John’s despair becomes so great he is at the point of ending his life.

It’s at this moment that his son, who is tagging along with him in the street, tells him what a great dad he is. Recognizing he has his son’s whole-hearted love and support (something he never had from his own father), John becomes aware he has received a secular kind of blessing, an affirmation of his self-worth. As Ralph Waldo Emerson would describe it, “Belief consists in accepting the affirmations of the soul; unbelief, in denying them.” John realizes that the love between him and his son is greater than any trauma or tragedy from his past, and his pride — which was nothing in the end but fear of failure — falls away, and with this he is able to reclaim the love that his family is waiting to give him.

The Crowd is immeasurably helped by the performance of the two leads. John Murray, chosen because the role called for an actor with virtually no artifice, gives one of the greatest of all performances in silent film. Eleanor Boardman, whose prior films typically cast her as a sophisticate, beautifully portrays a simple woman progressively worn down by life, but still doing everything possible to keep her family together. For its use of technical aspects: use of moving camera, forced perspective, lighting, and for its understanding of story structure and thematic content — for its ability to use — with ease and facility — every effect, every technique at that point understood and learned by filmmakers to tell a story, The Crowd stands as a crowning achievement in the art of film in 1928, the year it was released.

The Crowd is immeasurably helped by the performance of the two leads. John Murray, chosen because the role called for an actor with virtually no artifice, gives one of the greatest of all performances in silent film. Eleanor Boardman, whose prior films typically cast her as a sophisticate, beautifully portrays a simple woman progressively worn down by life, but still doing everything possible to keep her family together. For its use of technical aspects: use of moving camera, forced perspective, lighting, and for its understanding of story structure and thematic content — for its ability to use — with ease and facility — every effect, every technique at that point understood and learned by filmmakers to tell a story, The Crowd stands as a crowning achievement in the art of film in 1928, the year it was released.

The Crowd also strikes new ground in what would later be called modernism. With its interest in the emotional lives of its characters rather than with plot and, with its fragmentary assemblage of a typical life of an ordinary family, the film invites comparisons to other modernist works by writers such as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. The Crowd even manages to be subversive. Vidor’s inclusion of a toilet in the scene of their cramped apartment is as shocking in its own way as Henry Miller’s use of ‘unprintable words’ in Tropic of Cancer. Louis B. Mayer famously hated the film because of the bathroom scene — he called it that “damn toilet film.”

These subversive qualities had their repercussions; the studio, not knowing what they had, delayed the release of this film and with this delay (which coincided with the public’s sudden interest in talking pictures), and with the studio’s lack of support, The Crowd failed to gain the sweeping recognition that it might otherwise have achieved. Although critically acclaimed, The Crowd is often brushed aside when talking about important films of its era. Having no major stars and with no easy way to describe or sell the film, The Crowd has an odd ‘orphan’ status among the films of its era — outside of festivals or film school, few people have seen it, at least on a big screen.

Because of this history, The Crowd is perhaps more important in its influence on future filmmakers. The Italian directors saw in King Vidor’s work a populist vision of the common man, the template of their vision of neorealism. Vittorio De Sica himself described The Crowd as the first ‘neorealist film,’ and freely admitted he used elements of this film for Bicycle Thief and Umberto D. Roberto Rossellini is quoted as describing the ‘unforgettable impression’ of The Crowd made on him, stating that watching the film “really struck me and put me on the road toward truth, toward reality.”

And who can forget Billy Wilder’s rethinking of many ideas from this film, when he made arguably his best picture, The Apartment, even playing direct homage to the film by recreating The Crowd’s opening scene of the New York skyline panning into a dissolve of endless desks manned by robotic workers?

And yet there is more to The Crowd than merely a summation of its artistic achievements or its importance in shaping the future of filmmaking. When John learns to accept his limitations that he is just an ‘ordinary man’ (even to rejoice in this realization — because with this insight he acquires a particular kind of freedom), The Crowd is offering an update of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which also celebrated the freedom of the ordinary man. To conclude you are ‘nothing special,’ to accept your fate as one of the many blades of grass in a field stirred by the wind, is to see the world with new eyes.

In his essay ‘Inside The Whale,’ George Orwell describes Whitman’s insight that by acceptance of our ordinariness, there is a new-found joy of discovery — despite all hard knocks, the disappointments, all the pettiness of life, one can still find “that he is enjoying himself…” Whitman was writing in a time of national expansion and for many, unparalleled prosperity, but more than that, he was writing in a country where “freedom was something more than a word.” Orwell however, offers a cautionary conclusion, “Luckily for his beliefs, perhaps, he died too early to see the deterioration of American life that came with the large-scale industry and the exploiting of immigrant labor.” The Crowd is offering a current appraisal of the boundless optimism of the American Dream as envisioned by Whitman: Yes, the freedom to pursue your dreams is still part of our nation’s founding principle, but that dream is bounded by many barriers, both visible and invisible, and perhaps for most of us, the important part of living each day will be the ability to appreciate the small, simple things in our daily life, such as the gratitudes and affirmations we get from friends and family.

As I walked out of the theater, I saw Kevin Brownlow and confessed to him that this was my choice for Best Silent of All. He smiled, and said: ‘Mine too.’ We all know that Abel Gance’s Napoleon is the film that Brownlow has made into a career, and Kevin Brownlow has forgotten more films than I’ll ever see … and maybe he was caught up like I was, in the spirit of the evening.

Even so, for me, his answer was a thrilling validation. There are many Best Silents of All, and one is permitted to change one’s mind–as often as one wishes–for which film to award the title. But for me, even though there are many great films out there, I will always come back to The Crowd as the ultimate achievement of what can be done in the wonderful and often neglected art of silent film.

13 thoughts on “The Crowd – The Best Silent Film of All?”

Pingback: The Silent Movie Day Blogathon | Silent-ology

I’m in the middle of reading King Vidor’s autobiography. He talked about how he specifically cast Murray because he was unremarkable and did not have a face and persona already recognized by the public. But he did think he was talented. Not too many years later he ran into a derelict man on the street only to recognize him as Murray. He offered help and Murray sneered at him. And that was the last time Vidor saw his star before Murray passed away from a tragic death.

Hi SE,

I also read Vidor’s bio where he talks about casting Murray and what happened to him afterward.I think Murray was very talented and the combination of talent and not having a face recognized by the public worked well aesthetically but probably hurt the box office for THE CROWD, as Hollywood was a star system as it is now. If you want to see another great Murray performance check out William Wyler’s THE SHAKEDOWN, from 1929.

MGM recycled parts of the skyscraper sequence from The Crowd in a number of films – The Easiest Way (1931), Speak Easily (1932), What! No Beer? (1934), and probably others. Hard to say whether that testifies to their respect for the film (it’s a wonderful shot) or their disappointment in it (wonderful shots do not a commercial hit make).

It wins my vote for the greatest silent ever, too.

Although MGM didn’t make as much money from THE CROWD as they would have liked, that doesn’t mean the insiders (that is, the film community in Los Angeles), didn’t appreciate what they saw. They remembered being impressed, and when the time came for something similar to that shot, why not use it? And the studios developed over time a big inventory, so shots used for one film were fair game for whatever came next. That was true for everything: musical cues, props, wardrobe, even hairpieces!

When TV came around, the need to cut costs was even greater, so even more was borrowed – a “train-spotting game” has evolved when you can ID a prop from film to film then from one TV episode to the next.

For years that incredible tracking shot up the front of the skyscraper was missing from the studio print of the film due to its being removed from the negative for use as stock footage by many companies. Only due to a collector having a complete print of the film was that shot restored. A friend of mine gifted a print of that shot to King Vidor, whose own personal print was missing that part.

I didn’t know that. Thanks for the “Be Kind to Film Collectors” info!

The first time I saw THE CROWD I was stunned, I can see why you’d choose it as the greatest silent. Thank you so much for contributing this thoughtful post to the blogathon, Lokke!

Thank you! It was a pleasure to write an essay about a film that means so much to me personally.

According to author Scott Eyman, the film actually turned a tiny profit (under $10K) to the studio, due to MGM’s use of “block booking.” Thalberg said to Vidor when the director warned him that it “probably would not make a dime,” that hits like THE BIG PARADE helped pay for little films like THE CROWD. Mayer must have had some really bad memories of toilet use to be so obsessed with the WC in the film, going so far as to telling Vidor that SUNRISE was getting the “Best Artistic Achievement” Academy award because he pushed for the Fox Film over his own studio’s film due to the showing of the toilet.

Yes, I had read about that discussion between Thalberg and Vidor. There are many reasons that THE CROWD underperformed, one being that the country was awash with a lot of great movies that were released that year, and talkies were just around the corner. But one legit reason was that there was no star actor/actress attached to the project. Ironically, that is probably a major reason no one wants to go through clearing the rights and restoration expenses to put it out now, no one sees any profit in the time and expense. 10K may have been a marginal profit when it released, but it is entirely possible that today the net profit for a new release on DVD would be LESS than 10k, which tells you all you need to know about about the uncertain future of these films as purchasable items in physical media.

I know the toilet story gets a lot of attention…my instinct is that the story is painfully correct. That era was just catching a holdover of Victorian prudery and Mayer seems JUST the kind of person to me that would be both vindictive in his anger of the display of the toilet and compulsive in his desire to punish Vidor for showing it. Or in other words, Mayer seems to me very much like the professor in The Blue Angel, whose anger against the caberet staff serve only to signal his own interest in the world of the demimonde.

I have not seen many silent films but I recently watched The Big Parade and tonight I watched The Crowd. I found both to be excellent with The Crowd being the better of the two. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and knowledge of the films history.