First an explanation: I don’t like watching movies on TV and if there is a movie I’ve never seen before, I go out of my way NOT to watch it until I can see it on a big screen first.

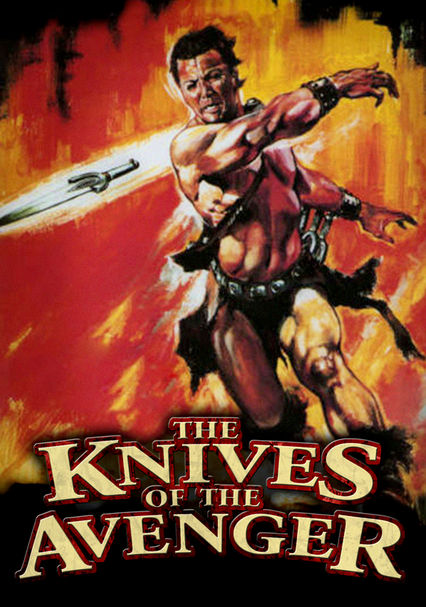

This rule goes for almost any movie made before 1980, after that the editing and photography of film starts to become deliberately matched up for TV viewing – so trying to avoid a movie when it’s actually been edited for a tv market would be pedantic. No, I’m talking about Classic Hollywood Era films clearly made to be seen in a movie theater on a big screen. This policy paid off in a big way this week when a local repertory movie theater screened Knives of the Avenger (1966).

Legend has it that Bava was brought in to direct Knives of the Avenger when the first director was fired and the production ran out of money – the legend goes on to say Bava rewrote the script and shot the movie in six days. And as far as I’ve been able to determine, this legend really happened, or close enough, anyway. And as I watched Knives of the Avenger, my reoccurring–even my obsessive thought was: My God – to get a film that looks this good in six days ESPECIALLY with almost no money available – that’s amazing, even for Mario Bava.

All I can say is that every penny, every lira, every centime, every sou … even every Burmese Pya and Uzbek Tiyin … that could be found in this next-to-nothing budget of this film – is up there on the screen.

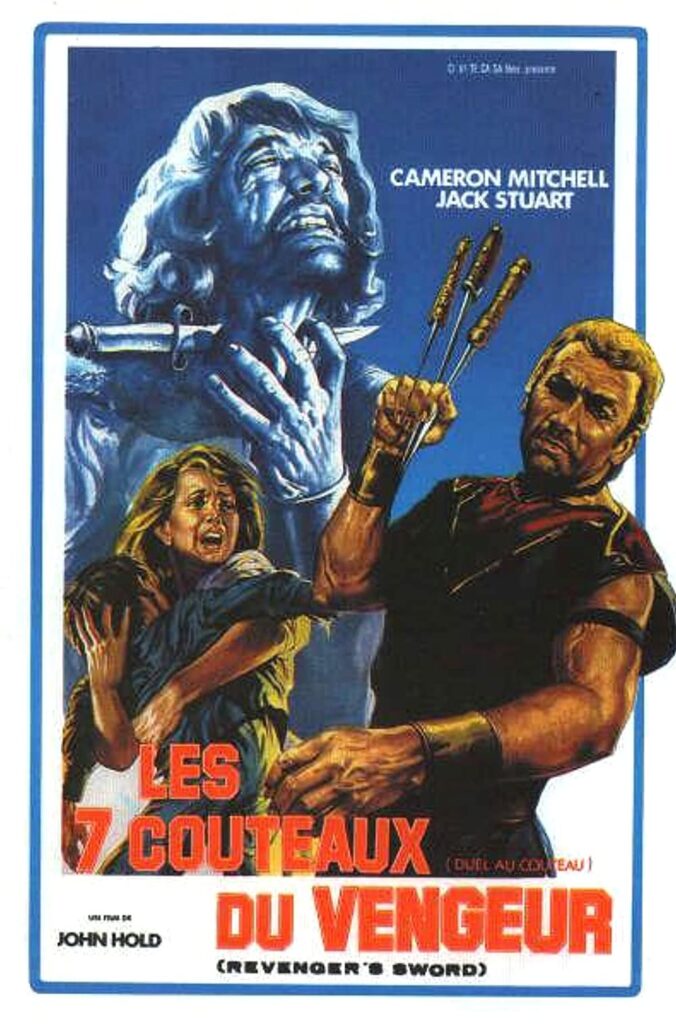

Knives of the Avenger is a sword-and-sandal film about Rurik (Cameron Mitchell) a mysterious Viking who arrives at a farmhouse and finds himself protecting a woman and her son from marauders. Soon we learn that the woman, Karan, (Lisa Wagner) is the king’s daughter and is in danger from the evil knight Hagen (Frank Ross) who is plotting to take over the kingdom. Rurik, a formidable warrior but a man who has his own secrets to hide, becomes the guardian of both Karin and her son, and accepting the role their protector, sets out to kill Hagen and bring peace back to the land. And as the story advances, we see the boy Moki (Louis Polletin) start to emulate Rurik, and faster than you can say ‘Shane’ we are pulled into a world where the boy is initiated into a familiar mythology of redemption through violence.

These sword and sandal films are all about the joy and wonder of telling a story. Werner Herzog talked about his love for these simple straight-ahead films, calling them a ‘movie movie’ (I tried to find a source for this quote and can’t, perhaps he brought this up in one of his talks I’ve attended … if anyone can source me, I’d appreciate it). Anyway, it’s a great description of Knives of the Avenger. It’s a ‘movie movie,’ full of joy and wonder, and even better, we get to see Shane retold as a Viking warrior story, with Cameron Mitchell holding up his end surprising well as a Norse incarnation of Alan Ladd.

The archetypal story is compelling, and the actors pick the right scenes to wring every morsel of emotion they can from their roles, but for me the best part of the film is the photography. By using camera placement, filters and gels to generate an epic feeling from the barest of sets, costumes and props, the look of this film begs to be seen on the largest screen possible. It probably looks okay on television (and who knows how many reviews of this film on the Internet are from this perspective, probably all of them), but on a big screen the landscapes and vistas are often achingly beautiful. Of all the Bava films I saw during this retrospective, this was my biggest and happiest surprise, and the one probably hardest to truly appreciate on anything except watching it on a huge movie theater with a rowdy, appreciative audience.