It’s a crowded ferry taking people away from Coney Island, and Dorothy Haley (Sally Eilers) is tired of being hit on by the guys on the boat. When she complains to her friend Edna Driggs (Minna Gombell) about it, Edna gives her a challenge: why not switch the tables and try to chat up a sourpuss who is hanging out by himself on the other side of the ferry? The two young women go over to annoy the young man, Eddie Collins (James Dunn), and after cracking wise for a few minutes they all become friends – the girls are happy to find a guy not on the make, and he’s happy to find two women can dish it out as well as they can take it.

Later, Eddie takes Sally back to the tenement where she lives, and they sit on the stairway, talking. She likes him too much to say goodnight, and Eddie is too shy to do anything about it. While they chat on, a woman stumbles by them, shock on her face. She goes to a nearby phone, makes a call, and explains haltingly on the phone that a parent has just died.

This scene is so natural, so believable, and must have been SO routine in this era, where a tenement building was essentially one large extended family, that with this deft, sideways move away from what we expect, Borzage elevates a standard boy-meets-girl romance into a story about the human condition.

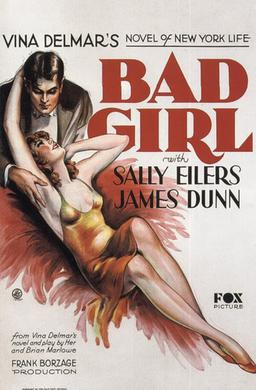

Bad Girl is obviously a pre-Code film by the date of its release, 1931, but I can hardly think of a Hollywood film from this era that is LESS salacious, by contrast the film approaches love and sex as a serious subject, and does not shy away from the fact that premarital sex happens. When it does between Eddie and Sally, her angry brother calls her a ‘bad girl,’ hence the title of the film, a title that becomes increasingly ironic as it’s clear to everyone her brother is a hypocrite.

As we follow Eddie and Sally down life’s road: marriage, issues about money and jobs, and having a child, at first we might be following a version of King Vidor’s The Crowd, but while Vidor’s film picks up speed and becomes more schematic, Borzage slows down the pace, and the story turns another unexpected direction, away from melodrama, and toward the routine and the mundane insecurities that can arise from the most petty and common injustices.

This film has many wonderful scenes (Borzage won for best direction this year, and this film won the Oscar for best script), for example, the opening moments of the story, with Sally Eilers walking down a stairway in a bridal gown, has one of the best humorous reveals of any film I’ve seen from the 1930s. A later scene with a ward of new mothers is beautifully constructed, as Sally, who is nervously waiting for her infant, studies the other women in the ward, realizing that each woman is taking in this life-changing event in her own way: one woman – eyes closed in happiness, another woman singing an Italian lullaby to her child, a third woman with a face filled with fear and uncertainty. By observing these other women, Sally has the realization that she is part of something bigger than herself – to paraphrase John Dunne, no man, no woman, and no child is an island, we are all part of a larger and more mysterious whole.

Borzage films are often the exemplar of the ‘heart-on-your-sleeve’ romance, and he frequently used melodrama as the vehicle for these pursuits, but in Bad Girl, he avoids flagrant melodrama except for a brief segment involving a boxing match and what happens in the ring produces such a nice plot twist that the change in tone is quickly forgiven. Borzage steers Bad Girl toward a genre that would later be called social realism, and results in making a film close to what Ozu was doing at the same time in Japan.

Stating that Borzage was making an Ozu-like film requires one to do some arithmetic. Borzage was nine years older than Ozu (he was born in 1894, Ozu in 1903), but this translates to a 14 year head-start in directing movies, crucially at a time when the language of film was being fully developed.

The young Ozu played hooky watching movies instead of going to school, in particular, he was a huge fan of Borzage, so much so that in his first surviving silent film, Days of Youth: A Student Romance, there is a 7th Heaven movie poster on the wall of one of the student’s lodgings.

So if you look at the timelines of the two men, instead of stating a Borzage film has an Ozu-like quality, it’s more accurate to reverse the comparison – Ozu’s films have a Borzage-like quality, and here’s my reason why that is the case:

For Borzage, it was important to him that the audience became invested in the story’s characters, and to achieve this goal, he was attentive to the film’s emotional landscape.

If the physical process of making a film produces a physical landscape – that is, the camera records action that happens from scene to scene, along with depicting the location of where it takes place, there is also an inherent emotional landscape that the audience navigates by watching how the emotions and feelings of the characters change from one scene to the next. This is done by a variety of techniques, such as filming actor’s faces, body movements, employing acting business, by music or the spoken word – usually by combinations of all these methods.

Whenever he could, Borzage made a point to foreground this emotional landscape. In practical terms, that meant to slow down the action, especially at the beginning of the film, and give the audience time to see the characters act and react to each other. He was willing to give up plot and especially pace for this to happen.

Ozu took this style of filmmaking, and ran with it, typically downplaying the operatic possibilities of a story, choosing instead to follow a more natural approach. But if one looks at these director’s filmography, it’s easy to see that they simply tailored this approach to the particular needs of the story. Borzage gave Bad Girl a more naturalistic sensibility because that’s what the story called for. And if Ozu wanted to make a film like Dragnet Girl, he could ‘out-melodrama’ anyone.

So instead of trying to come up with how the two directors were different, perhaps it’s more helpful to see how they were alike. Whatever their minor differences, Borzage and Ozu were quintessential humanists, emphasizing the value of human life and the power we have both as individuals and as a collective society to take care of each other.

Which is the conclusion of Bad Girl. All of us will be cuddled up someday in our own version of a stairway – nice and cozy – when out of nowhere, a stranger will come into our lives with some great need or tragedy.

And then it’s up to us whether we just watch, or offer to help.