If there ever was a Hollywood filmmaker who resists the impulse for binary thinking, (good vs. bad, right vs. wrong), it’s John Ford. Saying Ford was a complicated man, full of self-contradictions both in his personal life and in his films, is like saying the sun comes up in the morning and that vegetables are good for you.

Yeah, John Ford was a complicated guy, but so what?

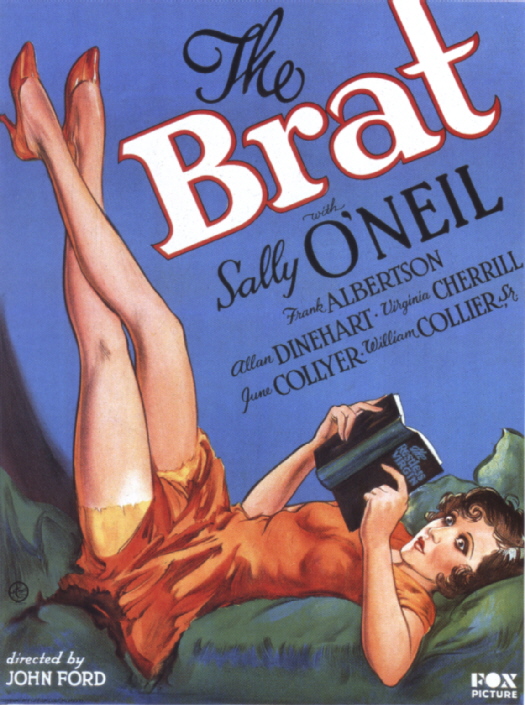

The ‘So what?’ question was at least partially answered while I was leaving a MoMA screening of one of his hardest-to-see films, The Brat (1931). The story concerns a street-wise chorus girl, ‘The Brat’ (Sally O’Neal) who is brought into a wealthy family in order that their bachelor son and novelist McMillan Forester (Alan Dinehart) can observe her at close-quarters and use her mannerisms as ‘local color’ for his next book. Soon the chorus girl’s presence shakes up the household and threatens to cause permanent changes in the stodgy and snobbish Forester family.

Originally a successful Broadway play first produced in 1917, The Brat’s plot is more than a little similar to George Bernand Shaw’s Pygmalion, which premiered in London four years earlier. In 1919 the play was adapted into a film starring Alla Nazimova (unfortunately lost) and with the coming of sound, Fox Film must have seen the chance to make money by retooling the story for a new audience.

In 2016, using badly damaged nitrate elements, MoMA restored The Brat to a DCP projectable image, and this is what we had just seen as the crowd filtered out of the room.

An elderly gentlemen, who must have been in the full bloom of curmudgeonliness, was in the exiting line ahead of me, and was not happy. “What a terrible film!” he loudly muttered to no one in particular, in other words, to everyone around him.

I let that one go. Chacun son goût.

“Just a miserable film. Worst I’ve ever seen.”

With that remark, to my way of thinking, he’d stepped over some MoMA-ish line that existed somewhere in the basement of this hallowed museum. It needed a response.

“The worst ever?” I answered, rhetorically.

“Worst acting, worst script, worst direction.”

“I disagree with you completely about the script. It takes Pygmalion and puts it into an American setting.”

“But they don’t do anything with it,” he said, now a little defensive.

“You didn’t like the middle of picture, when the Brat is on the rope swing?”

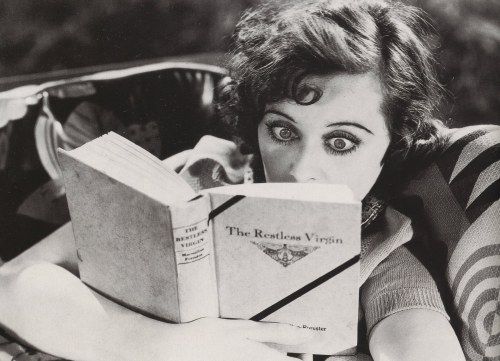

I was referring to an extended sequence when Sally O’Neil, playing the Lower East side version of Liza Dolittle shows plenty of leg, and then some – a common visual image seen in late silent and early talkies where male directors and cameramen seem to have discovered the female leg did not end at the knee.

“Yeah, that was okay,” he admitted, but she was such a bad actress.”

“But what about the cat fight afterward? I said, pressing the point. “It must have gone on for ten minutes. Even longer than Clara Bow’s fight in Call Her Savage.”

“You don’t understand,” he tried to explain, now deadly serious. “I saw Grapes of Wrath last week. What an amazing film – it’s so perfect and with such a message. And to go from that…to THIS.”

I felt myself losing my own argument, and changed my tack, adding a touch of academese to press the point:

“Maybe if we look at Ford’s films, each one…as a page in a diary. And if we watch each film, we can appreciate each film for what it is…as Ford grows as a director, he adds something with each film. To get to Grapes of Wrath, he had to do a lot of films like this.”

“I did like the beginning of the film,” he said, a crack opening in his defense.

“Yes, exactly. He had great character actors there, lifting up ordinary lines and making them good. Ford was learning how important it was to get the very best actor he could for every part.”

“Yeah, that part I liked”, he admitted.

“Here’s what I think,” I said, now on a roll, “I think Ford got to be a better director because he was full of so many contradictory impulses: he loved women, he was afraid of women, he was an arrogant bastard but at the same time he was full of self-loathing, he hated himself for drinking but he loved drinking and made all kind of excuses for it – he hated war but loved battles…he got to be a great director when he decided he could put all that self-contradiction up on the screen and let us sort it all out.”

“Yeah, okay,’ he said, “And other parts of this movie were good because I was able to sleep through them.”

“Exactly!” I said. “There’s something there for everyone.”

We parted in an unspoken truce, not friends, but surely not enemies – there was no final decision as to the worth of The Brat, instead we had a vigorous interrogation of what we had seen – in that sense we had a very ‘Fordian’ moment.

One thought on “A Curmudgeon Takes on John Ford’s The Brat (1931)”

I like how you turned what could have been lemons 🍋 🍋 into lemonade. Well done, lad!