James Whale is best remembered for his his horror films Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). But it’s important to remember that during his time at Universal, he directed other films that are also well regarded, including Waterloo Bridge (1931) and Show Boat (1936).

James Whale is best remembered for his his horror films Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). But it’s important to remember that during his time at Universal, he directed other films that are also well regarded, including Waterloo Bridge (1931) and Show Boat (1936).

But what about the rest of his films made at Universal – the ones that appear as tantalizing titles in his filmography but are not available to watch in any format? For decades they have been difficult or even impossible to see, especially on a big screen – but times are changing and after further restorations, these films are becoming increasingly available.

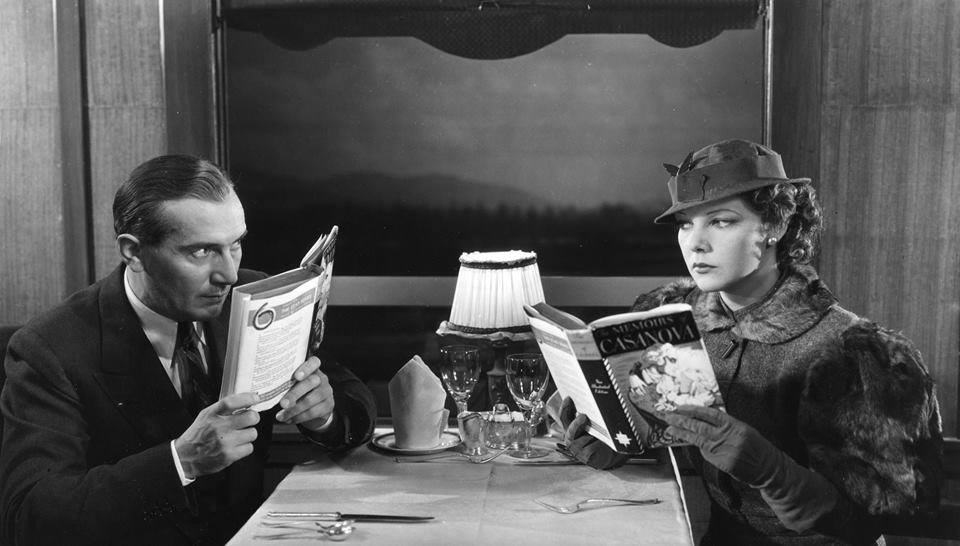

One of most obscure of these films is By Candlelight (1933). This is a bedroom farce, in which a nobleman’s butler, Josef (Paul Lukas), pretends to be his rich master in order to woo Marie (Elissa Landi), who he thinks is a lady, but who is a really a maid pretending to be a lady in order to impress Josef. Meanwhile Josef’s employer, Prince Alfred von Romer (Nils Asther) arrives and ends up being mistaken for the butler. Then things REALLY get complicated, and Josef and Marie take a road trip…

This is Lubitsch territory all the way, and for the most part, Whale shows a remarkable understanding of the mechanics of how to make farce work on the screen. There are two wonderful ‘ellipses’ of time and narrative which are vintage Lubitsch (or at least ones that Lubitsch would have enjoyed watching) – the first happens in an evening when Josef and Marie are alone together and drinking champaign and talking – the idea they are having a wonderful time, and perhaps falling in love is conveyed simply by watching on optical trick in which the campaign bottle goes from full to empty. The second, even better Lubitsch moment is when Prince Romer follows an angry woman at the casino – she stalks off down a garden path, he follows – and by the time the camera pans to them returning to the casino from other side of the path they are on friendly terms and joking with each other.

Even with these beautiful scenes, By Candlelight does not have the ‘glossy sheen’ one learns to expect in a Lubitsch production – the script, good as it is, needs a polish or two to make it better, and more importantly, By Candlelight doesn’t have the perfectly chosen cast that Lubitsch had for his films – at least the ones he made after 1932.

The major misstep in the film is the casting of Paul Lukas for the romantic lead role of Josef – he’s a good actor, but this is the wrong role for him – Lukas as an actor doesn’t have the charisma or natural magnetism you need to help explain why a girl like Marie would be naturally attracted to him. And his character’s need to take on a continental lover role to succeed in love really only makes sense if he starts the film as a shy, ‘Mr. Chips,’ kind of character, which Josef (at least as played by Lucas) is not. This is the main flaw of By Candlelight, and perhaps what turned this film from a potentially huge hit into an obscure title in a famous director’s filmography.

But miscast or not, Lucas and the rest of the cast are absolute professionals, they understand farce, and plunge into the improbable coincidences of the story with complete conviction, essential for this kind of film to succeed. Also, many farces start to sag somewhere in the second act, but By Candlelight finds new ways to add complications, so the movie achieves the rare distinction of getting BETTER as the story advances.

But most importantly, halfway through this film By Candlelight has an exceptional ‘interlude’ that is so unusual that it arguably overshadows the rest of the story. I recommend dedicated James Whale fans watch this film if only to watch this one scene so that they can place this unsettling moment into the context of his total collective film output.

What is this unsettling moment? About forty minutes into the story, Josef and Marie miss a train connection and find themselves stranded at a carnival in a small town in the south of France. The event itself (a romantically-involved couple becoming lost in a large crowd celebrating some kind of carnival) is the most routine of movie devices, and is often done to pad the story and to give some action and visual flair to the narrative.

But By Candlelight treats the scene not as a lighthearted affair but one with dark psychological overtones. The romantic female lead, Marie, is not just lost, but we have the sense that she is in danger. The masks worn by the townspeople are not any masks but are downright creepy masks. One could even say that with the lighting and shadows used, they are horrific masks.

And Whale chooses to linger over this procession of strange and unsettling masks, not moving on to another comic moment, but instead taking a directorial pleasure in prolonging the moment and putting Marie in a setting that could quickly be reframed in a horror rather than comedic genre.

The moment passes. Marie runs away from the revelers and the masks, and we resume the farce. But in many ways, this scene, which means almost nothing in regard to the rest of the film, is the most interesting part of the movie. Whale chooses to stop the story in order to ‘pause at the doorway’ of another genre in which the Other (to use a Freudian term) becomes uncomfortably close to ourselves – in other words, for a moment, Whales brings up the ‘is the real monster us?’ question – a topic he would explore with many of his other films. The effect of this interlude is to give us a brief glimpse with the possibility of ‘jumping genres’ from farce to horror, a potential switch that frankly looks a lot more interesting than the narrative we’ve settled down to watch. This specific use of the masks to raise the issue of the Other also prefigures a similar use of masks years later by Diane Arbus. An artist thematically connected to James Whale, Arbus would also spend a career exploring in her photography also exploring the implicit horror in the marginalized and Otherness found around us, even in the routine and banal.

Like a typical farce, all is well at the end – the Gordian knot of a plot is unraveled, and all the players are put back in the places where they should or needed to be.

And yet as I left the theater, I was thinking back to the scene during the carnival when the monstrous and threatening masks surround Marie…and where for a single, wonderful, scary moment, a horror movie threatened to escape into the theater.

Diane Arbus, Five Members of the Monster Fan Club, 1961