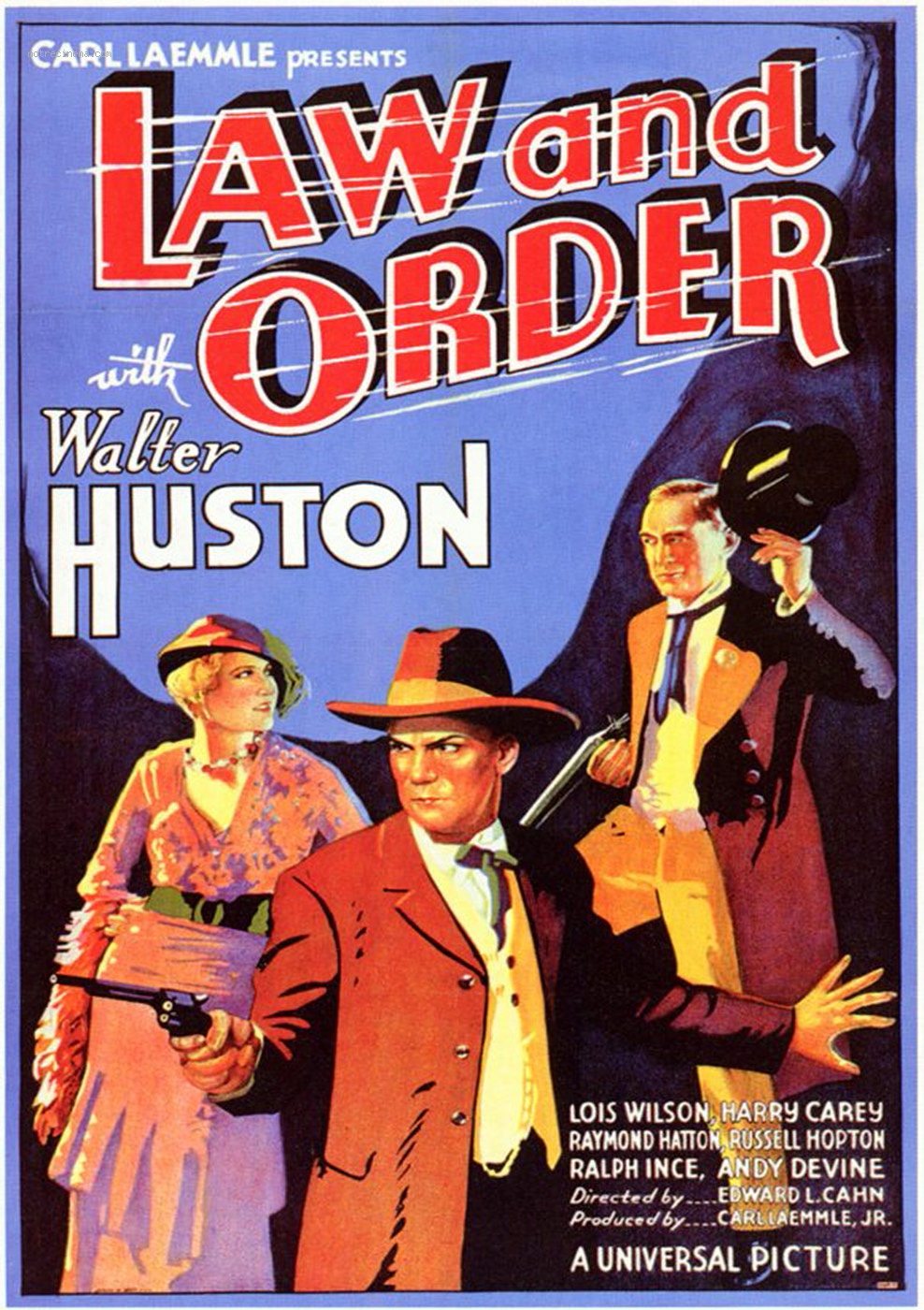

Pre-code films from Universal (many of them previously only available in duped copies or worn out prints) continue to be restored and made available for public screening, and one of the huge discoveries among these obscure films is Edward L. Cahn’s Law and Order (1932). Starring Walter Huston, with his son John Huston on the writing team for the screenplay, this early father-son combination is a must-see film for anyone who loves Westerns, Film Noir, or simply the rough-and-tumble world of the ‘anything goes’ pre-Code era.

The film is one of the first Hollywood efforts to recount the famous events that took place on October 26, 1881, in which Team Earp fought Team Clanton in the Battle of the OK Corral. Edward L. Cahn, the director of Law and Order, is one of the forgotten talents of the early 30s – in this film, he delivers an unpolished and fast-paced film which exactly matches the raw-edged Western story it’s telling.

This version of the Battle of the OK Corral changes the characters and the details of the story, but keeps the shootout climax intact. Walter Huston plays Frame Johnson, ‘the killin’-est marshal in the West,’ who has left Kansas to put his violence and gunshootin’ behind him. Little does he know that he and his loyal band have ridden into Tombstone, a town overrun by the evil Northrup brothers. The desperate townspeople convince Frame to accept their badge, and the more Johnson tries to avoid bloodshed, the more inexorably he and his band of brothers find themselves drawn into the battle of the OK Corral.

Law and Order had me onboard in just the first ten minutes of the film, when Frame and his tired and dusty friends enter a hotel room in Tombstone and the first thing Johnson does is to take a lantern and pull up the mattress of the bed to look for bedbugs. This act (a precaution that must have been routine for experienced travelers) gives the film an feeling of authenticity that few Westerns have ever bothered to try to achieve. After settling in the hotel, they meet the townspeople, who try to recruit Johnson and his band to save them from the Northrups. Johnson at first refuses, but one of the locals appeals to his vanity, saying “The Northrups say you can’t do it,” and with this challenge, Frame takes the bait and the badge.

Then comes the best scene of the film. Trying to bring law and order to Tombstone, Frame protects a young man named Johnny from a lynch mob (Johnny is played by a baby-faced Andy Devine, his cracked wonderful voice already in full flower). But afterward he learns that Johnny has killed a man, and the next day, the judge sentences him to hang. Johnny begs Frame to reduce his sentence, and Johnson weighs the awful consequences that will happen whatever he does. Finally he tells Johnny: “Son, you should be honored. Do you know you’ll be the first person in this county hung after a full court of law found you guilty? You’ll be the first person EVER in these parts to be hanged legally!” With this magisterial reframing of the situation, Johnson has taken a tragic event and imbued it with honor (not without a heaping smack of irony of course). This is writing on the highest level, and any fan of John Huston has to see this film if only for this one scene.

One of the strengths of Huston’s writing (he co-wrote the screenplay with Tom Reed) is that as he progressed as a screenwriter, he usually presented the theme of the story as an interrogation of a problem, not a polemic on how to solve it. For example, in Law and Order, the point of the story is not to show Good triumphing over Evil, rather it is about the problem of even trying to fight the battle. The script states almost from the start that the real problem with the Wild West is that guns have given the weak the ability (and perhaps even the moral authority, at least in their minds) of killing any person that disagrees with you. But then what do you do? Use violence to fight violence?

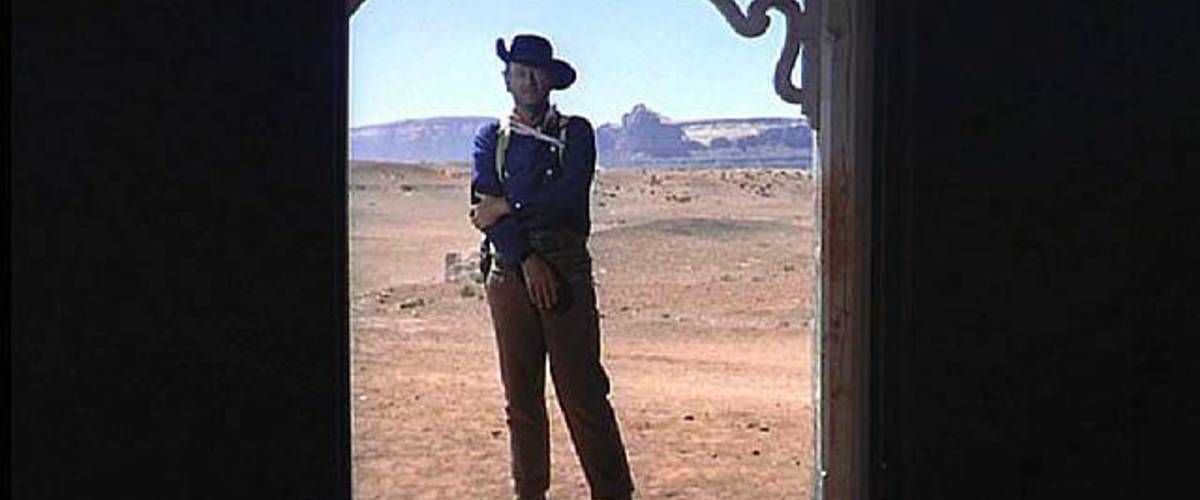

Frame Johnson knows how to do that. He is an archetypal Western hero, a man who by birth (or by experience) can operate in two very different worlds. Characters like Frame Johnson are sometimes called ‘liminal’ or ‘doorway’ characters, meaning they can operate in one world or the other, but are never completely home in either. One version of this kind of Western hero is ‘The Man Who Knows Indians.’ Often this man is a cowboy has lived with, or hunted alongside Native Americans, The epitome of this kind of hero is Ethan Edwards from The Searchers. Ethan is ‘A Man Who Knows Indians,’ a man with special skills and abilities, but also someone who finds himself out-of-place with either group. And as if to bluntly make this point, John Ford has Duke Wayne’s Ethan spending a lot of time lingering in doorways.

Another version of this character is ‘The Man Who Knows Evil’ – a man who has from upbringing or experience, has wrestled with good and evil as a personal demon – in other words, the best man to fight evil is a man who understands evil and is dangerously close to being evil himself.

Frame is this kind of hero, a man who understands the difference between right and wrong: he knows that killing is bad. But being on the side of the law gives him an ‘excuse’ to kill, and killing is something he’s very good at. And it’s hard not to do something you’re very good at, especially when everyone around tells you it’s the right thing to do.

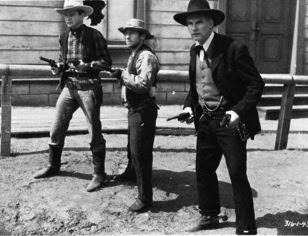

Frame knows fighting evil is what he does better than almost anyone, but he also knows that the battle will always come at great cost, perhaps even the ultimate cost of his own life. But despite these reservations, he is goaded into taking the badge. Now with at least a fig-leaf of moral authority, he relentlessly pursues a course of action which ends up with he and his friends battling the Northrups in the Battle of OK Corral in of one of the fastest and most lethal versions I’ve ever seen of this often repeated reenactment.

Frame emerges at the end the winner, but with all of his friends either hurt or killed, has anyone really won? The townspeople try to encourage him as he and his horse limp away. “You helped us. You helped our town!” “There’s always another town,” he mutters, in despair and disgust, and we know he is painfully right. Frame can leave the town, but he can’t change who he is. He will forever be the ‘The Man Who Knows Evil,’ a tortured soul who is always looking for a way to avoid violence, and never finding it.

Frame has failed in his quest, and with this failure, Law and Order marks a turning point of the Western, its downbeat message becoming one of the building blocks for a genre that would use elements of the Western to form a new genre, one that is now called film noir.

The Western is our country’s national myth, which simply stated is: we achieve spiritual renewal by a form of pilgrimage, specifically migration (westward), As a film genre, this myth would continue to thrive for decades and become the clearest representation of what we now call the American Dream. But concurrent with this positive, optimistic view of the country, dissenting opinions were also gathering strength. Fueled by post WW I anxieties, and then the Depression, this more cynical viewpoint would pick up steam as the 1930s wore on. John Huston was part of this ‘next generation’ of Americans, who had lived or served in Europe, and with this added perspective, were able to have a clearer understanding of the hypocrisies and paradoxes that lay underneath national myths and in particular, the search for the American Dream. These downbeat, interrogative challenges about American ideals and beliefs started getting more exposure by the late 1930s as countries begin rearming and major conflict looked increasingly inevitable. With this alarming development, many Americans must have felt that the ‘Great War,’ this ‘War To End All Wars’ had been a sacrifice made in vain. In a sense, entire countries must have felt they had been co-opted to take part in a quest that had ended in colossal failure. We had all become Frame Johnson, knowing that wherever we go, there will always be another town, another war.

Sadly, perhaps even tragically, the world was catching up to John Huston’s way of thinking.

In 1941, a John Huston-directed film, The Maltese Falcon was released to popular and critical acclaim. Other ‘noirish’ films had come before, such as Stranger on the Third Floor, even earlier versions of The Maltese Falcon had been released. But this Maltese Falcon had something these earlier films lacked. Huston’s version had all the hard-boiled meanness found in Dashiell Hammett’s novel, but there is something more going on – some writers have described this ‘something’ as nihilism or cynicism, but I see Huston’s The Maltese Falcon thematically as a statement for the need for courage – courage to see things as they really are, without illusion or artifice, and even more importantly, the courage to be wary of our own beliefs and self-created myths.

In the world of The Maltese Falcon, if we scratch our faith hard – hard enough to see through the thin layer of paint that hides the illusion of substance – we may find there is nothing underneath. And with that shocking, horrific possibility now at our fingertips, the world of film noir was truly born.

2 thoughts on “John Huston & the Origins of Noir: Law and Order (1932)”

Films Noir is the right word(s) at the right time, language still works.

Andrea, film noirs and films noir are both accepted by English dictionaries. The preferred form of film noirs is because of a concept of taking a compound word and finding the more important (or “head”) word of the two, which in this case is “noir.” Once that “head” is chosen, then it becomes the word that is then made plural. One can see that noir has become the more important of the two words to the point that “film” is now often dropped.

Here is more discussion of the issue-

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/English_plurals

“A distinctive case is the compound film noir. For this French-loaned artistic term, English-language texts variously use as the plural films noirs, films noir and, most prevalently, film noirs. The form films noir has no basis in either French usage or anglicization of French compounds. The 11th edition of the standard Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (2006) lists the anglicized version film noirs as the preferred style.

Unlike other compounds borrowed directly from French, film noir is used to refer primarily to English-language cultural artifacts; a typically English-style plural is thus unusually appropriate.

Again, unlike other foreign-loaned compounds, film noir refers specifically to the products of popular culture; consequently, popular usage holds more orthographical authority than is usual.

English has adopted noir as a stand-alone adjective in artistic contexts, leading it to serve as the lone head in a variety of compounds (e.g. psycho-noir, sci-fi noir).”