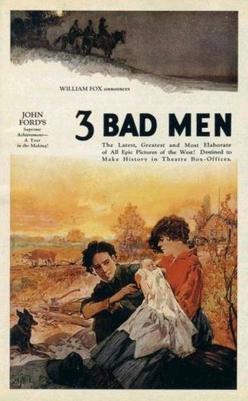

The story of a “good bad man” has been a staple of the Western since the genre was invented in the early years of cinema. And if one good bad man makes for a great story, THREE good bad men must be even better, right?

I’d say the answer to this question is…yes, IF the person directing this film is John Ford. The title of the film refers to three outlaws, and as the film opens we see their plans to steal horses from a covered wagon thwarted by another set of thieves who get there first. Chasing off the first set of robbers, the three bad men – “Bull” Stanley (Tom Santschi), Mike Costigan (J. Farrell MacDonald) and “Spade” Allen (Mike Costigan) – are about to kill the owners of the horses when they find out that the remaining survivor is a young woman, Lee Carlton (Olive Borden).

I’d say the answer to this question is…yes, IF the person directing this film is John Ford. The title of the film refers to three outlaws, and as the film opens we see their plans to steal horses from a covered wagon thwarted by another set of thieves who get there first. Chasing off the first set of robbers, the three bad men – “Bull” Stanley (Tom Santschi), Mike Costigan (J. Farrell MacDonald) and “Spade” Allen (Mike Costigan) – are about to kill the owners of the horses when they find out that the remaining survivor is a young woman, Lee Carlton (Olive Borden).

Instead of stealing the horses, the three men decide to befriend the woman and protect her from the advances of the lecherous sheriff, Layne Hunter (Lou Tellegen). Helping in this task is a Irish immigrant turned cowboy Dan O’Malley (George O’Brien), who the three bad men quickly see as a better romantic suitor for Lee than any other the other odd or rough and tumble prospects available.

A discovery of gold in the Black Hills turns a crowd interested in farming into a legion of hungry speculators, and a land rush into the Black Hills is organized. Layne Hunter wants the land and the gold, but even more he wants Lee Carlton, and the three bad men team up with Dan to protect Lee and give her a chance to build a new life in the Dakotas.

If anything, 3 Bad Men is too ambitious, with plots and subplots getting confused and in the way of each other. Also, the film has an episodic nature where one scene of comedy leads uncomfortably into another of serious drama. One has the sense that Ford is feeling his way here, without the sure hand he would show later in his career.

Some scenes work wonderfully. The quick turn from the three men from hardened outlaws to protectors is helped by the casting of beautiful Olive Borden as the romantic lead. Borden, whose smile could melt butter from thirty yards on a cold Dakota morning, has the star power to carry this part of the film – she was one of Fox’s lead actresses in the late 20s but became an early casualty of the sound era combined with a drinking problem. George O’Brien isn’t given much to do in this film except to look handsome (not much of a stretch for O’Brien).

The romantic leads in this film – if necessary – are quickly forgotten so that John Ford can concentrate on the more interesting three bad men, although under Borden’s spell of feminine charm, the title of the movie might better be translated as Snow White and The Three Rapscallions. As the story progresses, Ford changes the focus of the story to a more epic-like sweep of the land rush itself.

3 Bad Men is arguably Ford’s best surviving silent film, but if you need any reason more than that to see the film, it is for what I will call “The Shot,” which may be the most iconic found in any of Ford’s silents. The Shot happens just as the land rush starts, when a couple become so involved with their wagon that they leave their baby behind, in danger of being trampled by the following horses. The child is scooped up just in time by a nameless cowboy who sees the danger, and tragedy is averted, but not before Ford gets to juxtapose the most personal shot possible (a baby in danger) matched up against the quintessential epic-like scene of a thundering hoard approaching. The question in my mind is: Did Ford see Potemkin before shooting this scene? Ford is quoted as having the idea for the scene for a long time, having heard of it really happening in a similar context. On the other hand, Potemkin was released in 1925 and Douglas Fairbanks brought back a copy, which he showed to friends in the early summer of 1926, before 3 Bad Men was finished shooting. It could be coincidence, but if so, Ford and Eisenstein were surely thinking along the same lines. It’s fun to think this iconically American film has red, communist roots.

Item list:

1) Ford is already persistently framing his shots inside other frames: Windows, doors, canyon passages – every chance he can get, he frames his shots like paintings inside paintings.

2) The buddy picture genre is already firmly in place by the time this film was made. For those who don’t know this, buddy pictures typically a) use an opportunity for the buddies to disavow any homosexual ideas they might have for each other (in this film the three men make fun of a man who is set up as as a dandy or at least effeminate). And b) at some point these three ‘buddies’ use an opportunity to exchange body fluids – usually saliva (in this film at the time of ultimate bonding, the men all share the same stick of tobacco).