A prevalent cultural stereotype (perhaps less so now than a generation ago) is that since Germanic people have a limited sense of humor, they therefore are not good at making comedies. Of course the stereotype is ridiculous. Germany and Austria have been making comedies since the early days of film. After all, Lubitsch, Wilder, and many other immigrants to the U.S. showed Hollywood how to make comedies, and great ones at that.

As with most stereotypes, this view is caused by a lack of exposure, the problem is not that Germans have no sense of humor, it’s that German comedies have such a hard time getting seen by English-speaking audiences. It’s hard for any German film to get a widespread release in an American cinema, and pigeonholing a film as a comedy just runs against cultural prejudices that make it even a harder sell.

A film that in 2016 managed to “crack” this Germanic glass wall is a “screwball comedy,” Tony Erdmann, a German/Austrian co-production, directed by Maren Ade, and starring Peter Simonischek and Sandra Hüller. The film was named the best film of 2016 by Sight & Sound, won numerous awards, and finally beat the jinx of being German-language comedy AND a film that Americans could actually see in a movie theater.

The film is about a prankster father Winfried (Peter Simonischek) who assumes a sort of alter ego identity (including a wig and fake huge teeth) when visiting his uptight corporate consultant daughter Ines (Sandra Hüller). If his daughter Ines is wound up tighter than a three dollar clock, the winding is about to get three turns of the screw tighter because just as she begins the implementation of her boss’s plan to fire local Romanians and outsource their jobs, her dad Winifried shows up at their business meetings & parties as a “life coach” complete with wig and teeth. From there we go to discos and oil wells and by the time we get to naked birthday parties, Bringing up Baby looks very tame by comparison.

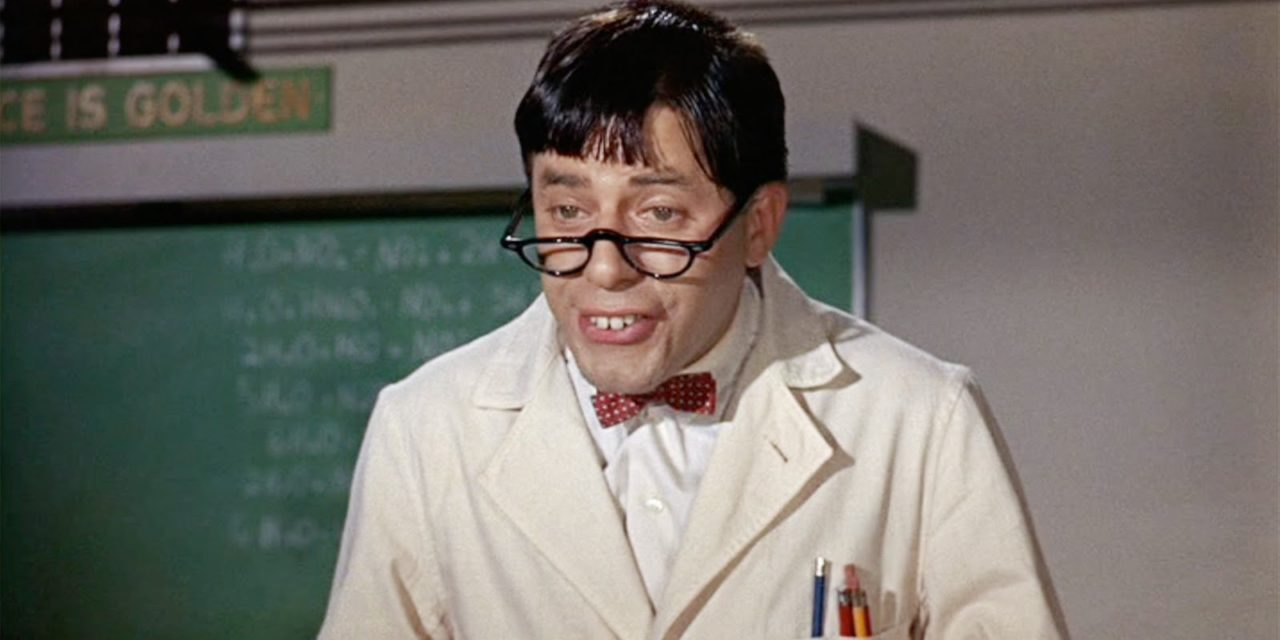

With a film almost three hours long, the parts are often greater than the whole, but many of the parts are terrific. My favorite is the nightclub scene where director Maren Ade inverts a famous scene from Jerry Lewis’s The Nutty Professor.

In Lewis’s film, after taking a Jeckyll and Hyde potion, his nerdy professor character is changed, becoming a suave, Dean Martin-type playboy who is a hit both with the ladies and gents.

In this film, Winifried walks into basically the same situation, but instead of a smooth sophisticate, he comes as his alter ego Tony Erdmann, with terrible wig and false teeth in place, and because he is so different and unusual – he is a huge hit. Director Maren Ade makes the point that for for Jerry Lewis to have really succeeded in the environment of a nightclub, he might have cut a far more dramatic entrance if he had come in as … surprise … Jerry Lewis, rather than another run-of-the-mill Lothario.

Screwball comedies – a type of farce – were “invented” in the 1930s by Hollywood after the production code started to actually enforce rules banning any explicit sex and violence. What the filmmakers did as a response to these rules was to make stories featuring characters with strong personal goals, but who were somehow blocked or prevented in achieving their interests or desires. These barriers could be external (social convention or the law) or internal (their own personal flaws). A screwball comedy is generated when these characters try – by whatever means necessary – to get around these rules, usually leading to mayhem and chaos before these subversive elements are reconciled to a conventional norm, such as a wedding, or in a more minor key, the gift of personal insight.

In the case of Toni Erdmann, (and let’s remember that the label of “screwball comedy” for a 2016 German/Austrian production is more of a term of convenience more than one of accuracy), the conflict is a long-standing rupture of intimacy and trust between father and daughter, who have been traumatized in the past, and have both adopted a variety of coping mechanisms to deal with the pain. By the end of the film, the father and daughter reach a reconciliation – she’s learned to loosen up, and he understands the need to stay in the real, non-fantasy world – at least most of the time.

If one wants to make an additional comparison between Toni Erdmann and The Nutty Professor, one can look backward in time and wonder about Lewis’ interest in doing a role that invited comparison to Dean Martin. Considering their long friendship, and then their feud, it’s hard not to come to some conclusion that Lewis wasn’t trying to “work something out,” in making The Nutty Professor. Perhaps both films suggest that role-playing and masks can be useful as “play therapy” – to test out parts of our personality that have been repressed because of fear and past events. These parts of ourselves are exiled, but they are never gone, they linger on in the cobwebbed corners of our minds, yearning to return and make us complete as a person.

Toni Erdmann reminds us that we are all versions of Winifried and Ines, and all of us sometimes need to take a breath, step back…and be another version of ourselves – whether that means we need to put a mask on – or take one off.

3 thoughts on “Tony Erdmann Takes on The Nutty Professor”

This is a test.

This is a test response.

This is a response to a test response.