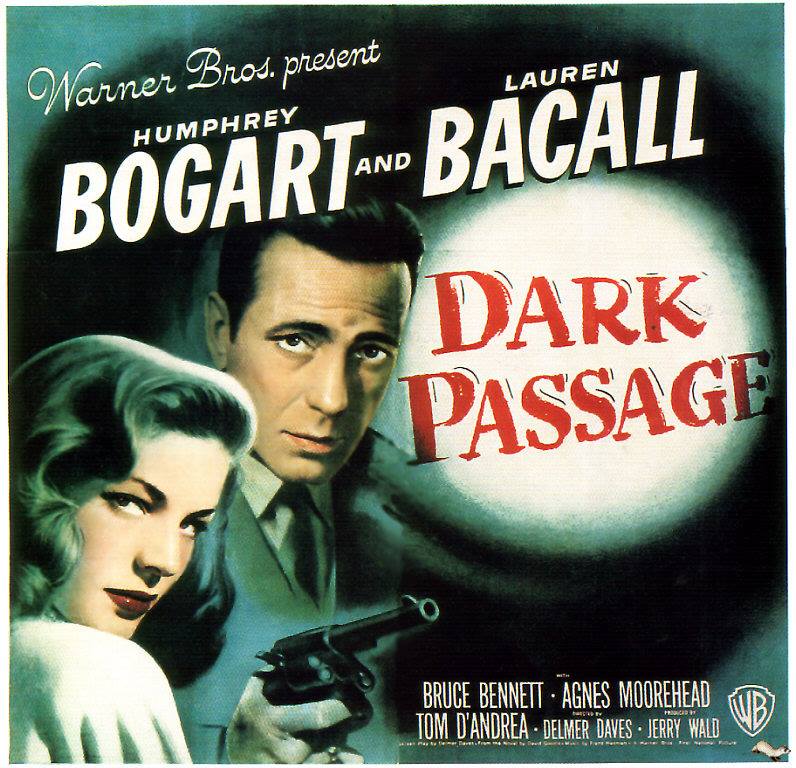

If it may please the court: The Case of Dark Passage, a 1947 crime drama, directed by Delmer Daves, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. It was the third of four movies the couple made together, and most famous for the first-person point-of-view for its opening scenes.

Dark Passage is one of the most distinctive and unusual Hollywood films of its era.

But is it—or is it not—noir?

And here is Judge Noir’s Ruling…

1) I really like Delmer Daves, as a writer and a director.

As a director, Daves always comes in through the writer’s door, giving his actors great scenes—he’s so generous with his lines, even the smallest part often has some memorable business or tag line. We remember the characters from his films, the cabbies, the waiters, the cops—each Straight Joe or Memorable Misanthrope has an interior life, and it adds a huge texture to this film.

But Daves is no slouch as a director and was the one person who made extended first-person POV work in a Hollywood film. He did it by using two techniques: the first is that this kind of POV is always MOTIVATED by something, in the same way you motivate a pan shot by following something moving—it takes your attention away from the choice of camera placement, diverting you instead to what the character is observing. The second thing he does is to give your eye a break by moving back to a 3rd person POV for a location shot or change of scene. It’s all very effective and never feels like a gimmick.

2) This is one strange movie. At some point, Daves (and the scriptwriter team) decided to ignore the normal Hollywood “realistic” film plotting scheme and go to Europe for their inspiration, and maybe even back in time to 1850, where French writers like Hugo and Alexandre Dumas were writing great novels. When you read these novels for the first time, it takes a little getting used to the idea of that plot coincidences are not bad writing, but are instead an accepted feature of the genre they were writing in (perhaps an extension of the allegorical novel that came before it).

Just as Pinocchio keeps meeting the Fox & Cat every time he steps out the door, just as all of Dumas’ characters keep bumping into each other the moment they turn a street corner, the characters in Dark Passage seem to living in a world of maybe 100 people, where running into who you know is not only expected but inevitable. It gives the film an eerie feeling, like the characters are walking through a dreamscape, and it pulls the story away from our Classic Hollywood roots, back to something more primal or elemental.

Just as Pinocchio keeps meeting the Fox & Cat every time he steps out the door, just as all of Dumas’ characters keep bumping into each other the moment they turn a street corner, the characters in Dark Passage seem to living in a world of maybe 100 people, where running into who you know is not only expected but inevitable. It gives the film an eerie feeling, like the characters are walking through a dreamscape, and it pulls the story away from our Classic Hollywood roots, back to something more primal or elemental.

3) This film deliberately violates the most basic rule of the postwar films that are now called noir—a rule eloquently summed up by Tom Neal’s character in Detour: “That’s life. Whichever way you turn, Fate sticks out a foot to trip you.” But not in Dark Passage, where fate sends Vincent Parry (Humphrey Bogart), a cascade of good fortune, for example, a sympathetic taxi driver, a great plastic surgeon who will change his face, and the most amazing stroke of luck of all – a woman named Irene Jansen, who has followed the trial and thinks he is innocent and is eager to help. And oh yes, did I tell you she’s an other-dimensionally Lauren Bacall-kind-of-beautiful? Well, okay, she IS Lauren Bacall but you get my point. Yes, Parry is innocent of murdering his wife, but as he admits himself, he sure has THOUGHT about it, and in the world of noir, that’s usually enough.

This film chooses to ignore the pessimistic, cynical zeitgeist that lay like a sooty, nicotine-tinged marine layer over America circa 1947, and instead gives us a “just” hand of fate, willing to give our hero a break and let him find his way to find his way to Peru to wait for Irene – and with this goal in mind, he recapitulates Ringo Kid’s famous dream of utopia spoken to Dallas in Stagecoach: “I still got a ranch across the border. There’s a nice place—a real nice place … trees … grass … water. There’s a cabin half built. A man could live there … and a woman. Will you go?”

And amazingly … Perry and Irene, and the rest of us—we all get there.

Now it’s time for Judge Noir to rule: While having many elements of noir, and in the right era, and EVEN starring Humphrey Bogart, this film is NOT noir, but if anything, is an extension of the Western genre, where that shining light, that “cabin in the sky,” is now farther south than just across the border, but just as inviting.

And yet—that dreamscape that Daves has walked us through—is still so odd, so troubling, so filled with people who are so trying to get something they don’t have—there is so much LONGING in this film, such a desperate desire to get something they don’t have and need so much.

And yet—that dreamscape that Daves has walked us through—is still so odd, so troubling, so filled with people who are so trying to get something they don’t have—there is so much LONGING in this film, such a desperate desire to get something they don’t have and need so much.

This need—this overpowering longing—it reminded me of a famous short story about a soldier with a noose around his head, standing on a bridge during America’s Civil War, a soldier about to be hanged, a young man who longs so much to live—and when he’s dropped … and the rope breaks … he gets his chance to make his break – he drops in the water and races for freedom, and he’s almost home … we sickeningly realize he’s still on the bridge and these are the last seconds of his life.

What if Dark Passage is Dave’s version of Ambrose Bierce’s “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” and Parry, rolling down the hill after falling off the truck, is having the last moments of his life before meeting his end at the bottom of the ravine, and in his last moments, he’s thinking about his escape and all the wonderful things that could happen to him (let’s call it a series of fortunate events), right before he hits the bottom of the ravine. And then, nothing—blackness. No more film in the projector.

If that’s the case, then Dark Passage truly lives up to its name, and we have watched the ‘noirest’ of all noirs.

7 thoughts on “Dark Passage – Noir or not?”

Wow, what a fascinating theory about all of Bogart’s tremendous good fortune. I don’t know now whether you’ve ruined the film for me, or made it that much more compelling.

Thank you Mr. Bengston. I think we can take refuge in what F. Scott Fitzgerald is reported to have said: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

I am a huge fan of your work and appreciate your post!

Very interesting analysis of a movie that has yet to capture me. The fact that the 100-person universe and all those coincidences work my last nerve might mean it’s something else that stands between me and the movie. I can’t enter into its world. But hey, I’ll keep trying: I *hated* L.A. Confidential the first few times I saw it, and Vertigo didn’t yield its glories until maybe my 6th viewing. But your theory about all those possibilities being his last few seconds mirrors mine of Vertigo, in which the entire movie is Scottie’s few seconds before he loses his hold at the beginning and tumbles to his death. I can’t support the idea, it just seems possible given the utter implausibility of the plot that follows, and the suffocating, inevitable horror of the denouement. …but I digress.

Lesley, we have traveled down similar ‘dark passages’ about this movie – I also had trouble with the multiple coincidences that happen in the story. Then two things happened: 1) I saw a Delmer Daves retrospective and saw a lot of melodramas, and 2) I also read some Hugo and other French writers from the Romantic age, pre-realism, and got into the ‘lingo’ of melodrama, in which coincidences are accepted and invited. It’s a world of opera, where things just happen by coincidence as a form of narrative shorthand. So with this in my head, I saw Dark Passage for about the fifth time and got a different vibe—abandoning my realist presets, I watched Dark Passage as a kind of opera, a dreamscape very much like “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” You can make the same mindset change with Vertigo, or even Laura (remember when he falls asleep next to the painting … perhaps the rest of the story is him dreaming! So once again, this essay is an invitation to watch this film with a different set of expectations—and maybe seeing a Daves melodrama from the 50s beforehand can put you in the right mood.

I saw this movie last weekend, and while it is enjoyably unrealistic for all the reasons you mentioned, your Bierce theory reminds me of how scary and uncomfortable to watch the initial tumble down the hill was.

Some fall/ crash imagery would help to reinforce this reading, and lo and behold – cue the fate of the two villains, although these scenes come rather too late in the film for us to bear the initla ones in mind.

Currently having a drawn-out argument with a friend of mine about what Noir really is. He insists it can’t be anything created after 1956, and the protagonist has to either die or go to prison. (What if there’s multiple POV characters?)

Me, it’s all about the look and feel, and the best Noirs are short stories and novels, not films–the films were just copying off the writers’ pages. In this case, one of the ultimate Noir-masters, David Goodis, who worked on the Daves film, which is reasonably faithful to the original. But I’d say the ending–though similar to the film’s–is a mite more ambiguous. Though the noose never snaps shut.

Either way–he’s lost his name, his face, his place–everything. Sure, he got true love, and that’s something. But if you take the ending literally, he’s still on the run for the rest of his life. If he’d been able to clear his name, walk free in his own country again–like Richard Kimble in The Fugitive (which Goodis insisted was plagiarized from Dark Passage, there was a lawsuit and everything), then it would not be Noir. But since all hope of proving his innocence died with Madge, and he will always be his wife’s murderer in the eyes of the world, the noose never terribly far away–Noir.

Goodis got even darker later on, and you want straight-up Noir, no better place to find it. His protagonists usually live, they don’t end up in prison–except one of their own making. But there’s always this sense of futility. You’re just delaying the inevitable, is all. Death would only be a relief for many of the Goodis guys.

This, for him, is a pretty cheerful ending. And would be, even if the noose snapped shut at the end. (Love the Bierce ref).

I mean, dying in the arms of Lauren Bacall may be Noir, but a guy could do worse. I don’t think Bogie would argue that point.

Hi Fred,

I basically agree with everything you said. It’s either a noir or a melodrama with noir elements (like The Big Sleep). If you think the last part of the film is a fevered dream of a dying man, this is noir all the way…if it’s a truly happy ending, then we are in The Big Sleep territory. Of course, there is always Clause 50 – the Grandfather Clause, which states that all Hollywood films from 1939 to 1965 in which any crime has been committed and which has ANY noir elements is “grandfathered in” and becomes noir by virtue of the year it was made. I like Clause 50. It makes the historical part of this noir question way less confusing. Hope this helps.