Graven Images: The Search for Drakula

No one in reading this sentence is old enough (or undead enough) to have seen this film, which uses the following quote:

“I am Drakula, the immortal one. I have been around a thousand years, and I shall live forever…Immortality is mine…Men can die, the world can be destroyed, but I live, I shall live forever!”

More than eighty years ago, a group of people made a film, called The Death of Drakula. This is a story about the search for what happened to this film, a search that ultimately led to a larger story not about the death and life of Drakula, but about the death and rebirth of a generation of Hungarian filmmakers.

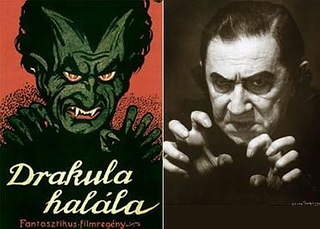

The German silent film Nosferatu has long received credit for being the first filmed version of Dracula. While researching Nosferatu, I repeatedly came across references of a Hungarian film, made possibly earlier than Nosferatu, titled The Death of Drakula, directed by a man named Károly Lajthay. Intrigued, I decided to travel to Hungary to research this film.

In my last blog, I talked about the first trip I took to Hungary in 1994 to research the ‘original’ Dracula film, The Death of Drakula.

The information I learned from this trip sent me in a number of different directions, including contacting the German and Austrian archives looking for traces of this lost film. The most productive part of the trip (with the help of the Hungarian Film Archive) was the unearthing of a Hungarian film magazine that had a one-page spread about the making of Drakula. The article had a tantalizingly brief description about the plot, but more importantly, included two production photographs taken while the film was being made for publicity purposes. At last we could at least get a glimpse of the Count!

Naturally, this information only wet my appetite, and when I returned to Hungary in 1996, I had three goals: 1) Research the trade magazines for information about the film. 2) Interview an actress who had worked with Lajthay, the man who directed Drakula, and 3) Spend time in the Hungarian Library looking for additional references to this film.

As I arrived back in Budapest, the changes in the ‘feel’ of the city—in just two years—were so profound that I wondered if I was in the same place. On my first visit, there had been a sense of being in an ‘open city,’ a term used in WW II when an army, usually because of being hopelessly outnumbered or outgunned, left a town unguarded, in the hope that the approaching army would not use bombs or use deadly force to occupy it. Because the Soviets had been in Hungary for decades, not years, perhaps a better way to describe what I saw was that of being in a prison in which the jailers had one day suddenly opened all the doors and disappeared, leaving everyone inside to fend for themselves. No questions answered, no explanations, no excuses, just abandonment. How could any prisoner in this exceptional situation feel anything but conflicted feelings of both relief and anger?

Two years later, this sense of an ‘open city’ was gone. My train had taken me to ‘just’ a picturesque European city. The portraits of Lenin and other communist leaders that were still hanging in hotel rooms and public places two years were gone. All the mementos—the cultural place markers of the communist rule in Hungary—had vanished.

While I understood the impulse to shrug off this terrible era of oppression, there was a quality of erasure about the era I found disturbing. It was almost like the Soviet occupation of Hungary had never happened. But what did I really know about any of this? I couldn’t read or speak Hungarian, and I concluded my reaction was a result of a naïve tourist trying to understand a profoundly complicated subject.

A photo of Mária when she was still an actress.

I got back to my research into what was probably the first Dracula film. I could find no one alive who worked on The Death of Drakula, but with the help of the Hungarian Film Archive, I interviewed Mária Szepes, a woman who, as a child actress, had been directed by Lajthay in another film. After her career as an actress was over, Szepes was enjoying a long and successful second career as an essayist and novelist.

With a translator provided by the Film Archive, we traveled to her apartment. Elderly, but in good health, Mária was comfortably ensconced in an apartment full of books, many of which she had written. After making introductions and talking about her work, I brought up the topic of the director of The Death of Drakula.

“He was more interested in women, horses and booze than in making movies.”

Her memories of Lajthay were not happy ones. Mária Szepes first met him with her parents at a Hungarian coffeehouse. Lajthay was full of promises about how his next film was going to be a huge success. “He was a great talker,” Mária explained to me, “more of a talker than a doer.” When Szepes arrived for the actual filming, the shooting was a disorganized mess. Lajthay, in Mária Szepes’s memory, was more interested in horses, booze and women than in trying to get the right shots. Because of this bad experience, Szepes dismissed both Lajthay and The Death of Drakula, “It could not have been a very good film. He was full of promises, and none of them happened.”

A photograph of Mária and myself.

While Mária Szepes was giving us useful information, time has a way of influencing and changing memories. Also, other directors, such as Tod Browning, were legendary for turning material from haphazard and disorganized shooting into compelling silent films. Mária Szepes had no memory of ever seeing The Death of Drakula, so her final conclusion as to its merits was as much conjecture as anyone’s. Whatever his talent, Lajthay’s film career did not survive much past the sound era. He worked sporadically in theater around Europe until he died at the age of sixty, in 1945. None of his silent films survive, and his story is the story of an entire generation of Hungarian filmmakers. Almost all of their films are gone.

My interview with Mária finished, I said my goodbye to this lovely lady, and later that day, wandering back to my hotel, walked into a demonstration. A group of old, gray-haired Hungarians were holding signs and gathered at a park. Holding a microphone, one of them was giving an impassioned speech. The advanced age of most of the demonstrators made it one of the oddest protests I’d ever witnessed. Someone who spoke English saw my puzzled face and came up to explain that the crowd had gathered together to memorialize the 1946 uprising. “But it’s such a small crowd,” I said. The stranger in street gave me a somber look. “Yes. Very small. For most Hungarians don’t know about what happened in ’46. They don’t care…they don’t know about any of this.”

My concerns about a lost film from the 1920s seemed petty by comparison. This small crowd—this visible challenge to a national amnesia of a hugely important post-WW II event—was happening before my eyes. My thoughts about memory being perishable was being acted out, not in the world of silent film, but in a world very close to my own time.

As I look over these words I wrote in 1996, 16 years ago, time has dimmed my own memory, and I am hard pressed to remember exactly what I saw. I remember the raw naked emotion of these few old men in the square, but little more. I Google key words and find a wiki article:

The Hungarian Revolution or Uprising of 1956 was a spontaneous nationwide revolt against the government of the People’s Republic of Hungary and its Soviet-imposed policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. It was the first serious blow to Soviet control since the U.S.S.R. forces drove out the Nazis at the end of World War II. Despite the fact that the uprising was not successful, it had a large impact and would come to play a role in the downfall of the Soviet Union decades later.

The revolt spread quickly across Hungary, and the government fell. Thousands organized into militias, battling the State Security Police (ÁVH) and Soviet troops…By the end of October, fighting had almost stopped and a sense of normality began to return.

After announcing a willingness to negotiate a withdrawal of Soviet forces, the Politburo changed its mind and moved to crush the revolution. On 4 November, a large Soviet force invaded Budapest and other regions of the country. Hungarian resistance continued until 10 November. Over 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet troops were killed in the conflict, and 200,000 Hungarians fled as refugees. Mass arrests and denunciations continued for months thereafter. By January 1957, the new Soviet-installed government had suppressed all public opposition. These Soviet actions alienated many Western Marxists, yet strengthened Soviet control over Central Europe.

Public discussion about this revolution was suppressed in Hungary for over 30 years, but since the thaw of the 1980s it has been a subject of intense study and debate. At the inauguration of the Third Hungarian Republic in 1989, 23 October was declared a national holiday.

So back in 1996, I had been watching a meager demonstration against cultural amnesia, not from any inherit apathy or lack of interest, but instead from a concerted forty-year effort by the communists to erase this incident from the hearts and minds of Hungarians. To this point, they were largely successful, and if the Soviets had stayed in power only another 20 years, this deletion of history would have been largely successful. My views about the erasure of memory were becoming more nuanced. The contemporary effort of the Hungarians to forget the Soviet occupation that I noticed in 1994 and 1996 were in a sense, a payback for all the years the Soviets had spent trying to make they Hungarians forget their own history.

My last task in Budapest was to spend a day in the National Budapest Library. I came with high hopes and an English/Hungarian Dictionary, but three hours into the task, it was clear that I was outmatched. Not knowing the language, I was forced to use key words as pictograms, and this is an extremely inefficient way to use a library. I spent the afternoon looking at newspapers (easier to translate) and after addressing the confusing point that the first run of the film in Budapest appeared to be in 1923, I packed up my papers and headed home.

Later, my contacts from the Hungarian Film Archive told me that other researchers found what I missed—definitive information about the film itself. Did I look in the card catalog under the wrong heading? Or maybe even the wrong card catalog? I don’t know, and in the long run, it doesn’t matter.

A year after I left Budapest, another Dracula scholar, Jenö Farkas, continued my search, but being Hungarian, had a leg up on the detail work. While in the National Library, he found a filmbook, published in 1924, titled The Death of Drakula.

Filmbooks attempted to translate a film onto the printed page to give the story a different form of accessibility to the public. Since these adaptations were frequently fleshed-out versions of the film’s script, the storylines in the books and films were usually similar if not identical. Filmbooks were then, and are now (in their modern incarnation as paperback novelizations) a popular way for those involved in the production of the film to make additional revenues.

With this book, Farkas was able to reconstruct the probable plot of the original film. Since this book is probably as close as we will ever get to seeing the movie itself, I am going to describe the storyline in some detail.

The story begins as Mary Land, an innocent sixteen-year old orphaned seamstress, lives by herself in a small mountain village in Austria. She visits a mental hospital once a week to see her adopted father, who has had a nervous breakdown after the death of his wife. On Christmas Eve, Mary receives word that her father’s health is failing. Her loyal boyfriend George, a local forest ranger, takes her to the hospital. Inside the hospital, Mary meets a once-famous composer who was once her music instructor. He has since gone mad and now claims to be the evil Drakula, spelling his name with a ‘k’ (perhaps to give the name a more local touch). Mary tries to talk to her former teacher. “Try to remember, Mr. Professor…I was there, second row…you stroked my hair as a sign of approval…”

Shaken by this encounter, Mary is then seized and abducted by two patients who think they are doctors. They tie her up on a table with the intent of operating on her eyes. The plot is broken up by the staff of the hospital, and Mary is untied. She arrives at her father’s side just in time for him to die in her arms.

Mary Land, spending the night at the asylum after these horrible events, has a terrible dream. Her music instructor, now calling himself Drakula, kidnaps her and takes her away to his castle. Twelve brides gather around her and escort her to a black magic marriage ceremony. Mary realizes that she going to be Drakula’s new bride. At the last moment, Mary lifts up the crucifix she is carrying around her neck. “The cross! The cross!” Drakula yells, backing away. The rest of the evil spirits are repulsed. Mary runs out of the castle and into the woods.

Photos taken from the trade journal match the filmbook storyline.

Half-frozen, Mary is found by friendly villagers, and they call for a doctor. As Mary hovers near death, Drakula comes to her bedside and tries to hypnotize her. He approaches Mary with “a hellish face, blazing eyes, satanic features and hands ready to squeeze.” The real doctor has been through a fiendish ride on a dark winding road to get to Mary. Now he arrives and with his help, Mary fights off Drakula’s mesmerizing gaze. A lamp overturns, and the house catches on fire. Mary again runs out into the cold night, but now she wakes up to find herself back at the mental hospital. Was this all a dream, she ponders?

Paul Askonas, the first screen Dracula.

Meanwhile the insane inmates are playing games in the hospital garden. “Funnyman,” a man wearing a pointed hat and thick glasses, has found a loaded gun. He aims it at Drakula, who seeing a chance to prove his immortality, urges the man with the gun to pull the trigger. “When the shot finally rang out, it penetrated Drakula’s heart and killed him instantly. His blood spilled out and left a bright red stain on the freshly fallen snow.”

Mary recovers, and as her fiancée George comes to pick her up from the hospital, they see Drakula’s body being carried out on a stretcher. Papers fall out of the dead man’s pocket titled “Diary of My Immortal Life and Adventures.” Mary does not want to see the diary, and George throws the book away. Mary never tells George of her terrible ordeal. She thinks to herself: was it all a dream, or did it really happen?

With this, the book ends, leaving us with a more contemporary question than interpreting Mary’s dream: how close was this printed book version to the film?

It’s useful to compare this narrative to the article about The Death of Drakula, which appeared in a Hungarian trade journal written in 1921. The journal includes two pictures from the film, one of Mary’s abduction and the other of the wedding. The details seen in the photographs and in the text match the storyline precisely. This evidence strongly supports that the storyline of The Death of Drakula book is close to what had been filmed three years earlier.

So the book is probably close to the script of The Death of Drakula, but this leads us back to the most important question of all: is this story close enough to Stoker’s novel to be considered the first Dracula?

One way to consider this question is to evaluate the story more as commentary on the pervasive impact of Stoker’s creation, rather than as a literal adaptation of the novel. The photos of ‘Drakula’ are similar to Raymond Huntley’s appearance in the stage play Dracula, which was doing great business in Europe at the time this film was made, and in that sense, Lajthay is evoking the image of Dracula as an evil character already familiar to the public.

There is no evidence in the filmbook of any deliberate attempt to associate Drakula with the historical Dracula, Vlad Tepes. Vlad was part of the Romanian history and culture, not Hungarian, and Vlad’s ties to Stoker’s fictional character are tenuous at best. However, it is an open question as to if this connection was made by some of audience familiar with the legends surrounding Vlad. Of note is that when the filmbook was published in 1925 it was published in Transylvania. Lajthay was also from Transylvania, which until 1918 was still part of Hungary.

The narrative from Death of Drakula models itself not from any historical event, but from the fictional stories circulating in the early part of the last century. Svengali-like stories of powerful dynamic men hypnotizing pure innocent girls were one of the staples of popular melodrama. Indeed, since Mary is kidnapped by her former music teacher, one could argue that the story is closer to Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera, than to anything Stoker visualized.

Still, there is the matter of the fangs. The front cover of the filmbook portrays a wonderful drawing of Drakula, displaying very sharp and deadly teeth. The image could be a display of wishful thinking by the artist. This would make it part of a long tradition of poster art and advertisements that promise more than is delivered.

Still, there is the matter of the fangs. The front cover of the filmbook portrays a wonderful drawing of Drakula, displaying very sharp and deadly teeth. The image could be a display of wishful thinking by the artist. This would make it part of a long tradition of poster art and advertisements that promise more than is delivered.

Or perhaps Drakula did have fangs, but only in the dream. If this is the case, the film itself begs the question of whether Drakula is real. This plot device appears lifted directly from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, of which this film has more than a passing familiarity. Freud was one of Vienna’s most famous citizens, and his influence can be felt throughout the story, chock-a-block full of symbols and neurotic dreams about substitute fathers.

An ad from a trade journal promoting the film.

Newspaper accounts confirm that The Death of Drakula opened in Vienna in February 1921. Nosferatu premiered thirteen months later, in Berlin in March 1922. On these grounds alone, The Death of Drakula is clearly the first film adaptation that has a connection to Stoker’s novel.

A reference book, with a probable publicity still from the film.

Perhaps the Austrians should get some of bragging rights as to which country produced the first screen Dracula. The film is an Austro-Hungarian collaboration, since the film was both partly shot and premiered in Vienna, and Paul Askonas (who played Drakula) is Austrian. This “Hungarian Dracula” has more than a little Germanic blood in his veins. According to records located by Farkas, the exterior locations of The Death of Dracula were shot near Vienna, and the interiors filmed in Corvin studios in Budapest. Paul Askonas was in many Austrian films in the twenties, but as these films did not reach wide distribution outside of central Europe, his work is obscure. Those interested can look for his brief but menacing presence as a butler in the 1924 German film The Hands of Orlac.

A trade journal reporting on the 1921 opening in Vienna mentions that the lead actress was played by a Serbian actress named Lene Myl. The film next resurfaces in Budapest in 1923 with the lead actress named as Margit Lux. Although this might be simply the result of a marketing decision designed to highlight different actresses, the possibility exists that Lajthay recut or reshot the film to star Margit Lux, making the 1923 film an alternative version.

An artist’s drawing of Margit Lux, now at the Hungarian Film Archives

Károly Lajthay wrote and acted in more than twenty films and he directed at least twelve. All the films he directed in the silent era are lost. The Hungarian film industry in the 20s was a victim of the bitter political landscape that existed in the country after the first world war. Internecine fighting and lack of money combined to cripple the chances for talented filmmakers to make movies in their country. Many quit the business or became expatriates. Lajthay went back to his first training with the theater and was away from film for almost twenty years.

Lajthay returned to filmmaking briefly before he died in 1945. He was involved in the production of two sound films. The second, which he codirected, was Yellow Casino, made in 1943. Yellow Casino is a comedy-suspense thriller in the Hitchcock tradition. A man has a jealous rage over a woman he loves, and finds himself in an insane asylum. (In Hungarian, “yellow room” is Hungarian for mad-house.) Artists frequently return to themes important to them, and this film, which happily survives, turns out to be a recasting of elements from The Death of Drakula. So although the original film is probably lost forever, Lajthay’s vision lives on in a remake of sorts.

WW I produced a complete destruction of the Hungarian film industry. If one can say that the America and the Western powers won the war and lost the peace, then Hungary lost the war AND the peace. The county briefly became communist; artists and actors long held under the repressive and controlling bit of the Austro-Hungarian war regime rejoiced at a chance for a new beginning. In only four months, Hungary produced more than thirty films. The country had an opportunity for the flowering of an art form that could have rivaled the art of Soviet filmmakers such as Eisenstein and Kuleshov.

After a short 133 days of (red) wine and roses, the honeymoon ended with a bang and a crash. The Hungarian Red army was crushed by Romanian forces, supported by anti-communist Whites. The result of this civil war produced a bitter, internecine struggle in which the artists who had declared themselves either communist or communist sympathizers (either from sincere beliefs or in order to work for the new Hungarian Soviet film studio) had to flee, sometimes for their life. This purge, combined with a growing anti-Semitic movement, produced an exodus of talent from Hungary only perhaps rivaled and surpassed by the flight of the Jews from the Nazis a generation later.

A caricature of Bela Lugosi on display at the Hungarian Film Archives

One happy outcome of this death of the Hungarian film industry is that the seeds scattered by this diaspora was to enrich the rest of the world. Kertesz Mihaly resurfaced as Michael Curtiz, Lukacs Pal became Paul Lukas, Korda Sandor became Alexander Korda. Another ambitious actor, Bela Blasko, working under a stage name Olt Arisztid, who had been organizing an actor’s trade union, fled to Germany, then to America, now with the name of Bela Lugosi.

This is all interesting as a history lesson, but to return to the question that started my search is the first place: Is the The Death of Drakula the first story featuring Dracula? Is it the first movie to describe what we now think of as vampires?

Vampires are quintessential seducers, and seductive men and women have been a staple of films from almost the beginning. With this very broad definition, you could find vampires lurking in many if not most films. In an attempt to be more selective, many vampirologists resort to more literal definitions to sort out the vampire from the vamp. Is he or she real or supernatural? For this film in particular, does Drakula have fangs, and does he suck blood?

On first consideration, The Death of Drakula fails this “bite ’em in the neck” litmus test. The film is not, in effect, a realization of the novel itself; it is more a commentary on the pervasive impact of Stoker’s creation. In only twenty-four years from the novel’s publication, Dracula is already familiar enough for Lajthay to use as a symbol of evil repelled by a crucifix.

Those who insist that their Counts live in coffins and suck blood can rest assured that the German Nosferatu still qualifies as the first attempt to film Stoker’s novel. The rest of us who like life with its complications and ambiguities can point instead to Hungary. It is only fitting for the country of the birthplace of Bela Lugosi to also have made the first filmed Dracula.

5 thoughts on “Graven Images: The Search for Drakula (part 2)”

Thank you for a fascinating essay. As someone engrossed with the vampire genre I find it saddening that we are likely never to see the film.

You ask the question of whether it can be classed as a vampire film, and I believe the elements described would certainly lead me to that conclusion – whether it is just the belief that.Drakula holds that he is the creature or something more.

Hypnosis was important within Stoker’s novel, of course; the mention of Charcot, the hypnosis of Mina to track Dracula and, of course, the effect that hypnosis had on Lucy, which transfigured the way she was as a vampire – in trance she died and in trance she is undead.

With reference to the crucifix, I don’t disagree that Stoker’s novel (and more importantly the plays thereafter) probably popularised the iconography with regards the vampire. It has to be remembered as well that George Méliès used a similar imagery in Le Manoir du Diable, though rather than a vampire it was Mephistopheles who is pushed back by a cross (and then vanishes in a puff of smoke). The film, of course, was released the year before Stoker’s novel.

I think it would be fascinating if the filmbook were to be translated and re-published (perhaps it has, and I am unaware of it).

Again, many thanks for the essay and for the effort of your search.

Nice work, Lokke! You get a gold star on your report card for this one.

Any chance you and Farkas could scan that filmbook and publish it? Good jpgs or a PDF can easily be converted to Ebooks these days.

Quite a very interesting and precise post. And quite an impressive investigation. I got the same question than Steve Hooley : is there a way to take a lool at the filmbook ? Did you have in mind (and the rights) to publish it ? That would be awesome !

Simply amazing detective work that helps complete the early DRAKULA jigsaw. It is up there with the production history of NOSFERATU and the rest.

The first 1898 translation of Stoker’s masterpiece was also into Hungarian – so they can rightly boast a range of firsts.

Imperative though that you bring it to the next level and publish the results of your research including copies of all surviving materials.

Thank you so much. Sorry it took so long to get back to you – I had done something to my website so wasn’t seeing any comments, until just now! Have lots more material and will publish when I can.